Farming special - Day 1: Suicide and mental health

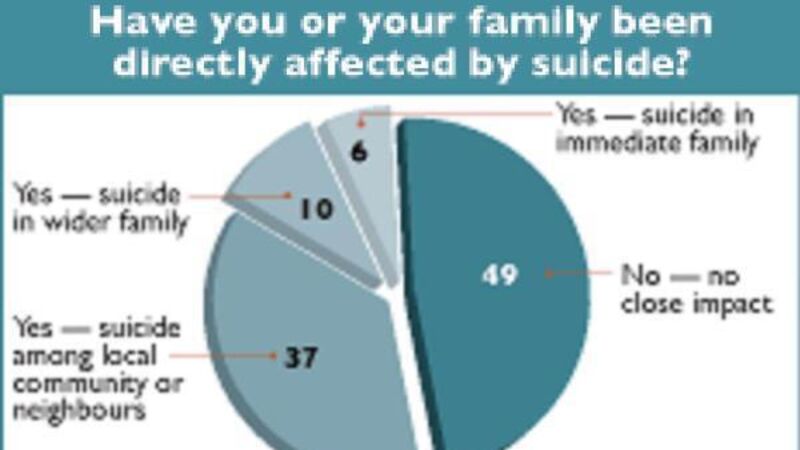

The Irish Examiner/ICMSA survey on farming attitudes found more than half of all farmers have been impacted by suicide, with 16% saying they had experienced it either in their immediate or wider family.

One in five farmers between the age of 35 and 44 said they had an immediate connection with suicide, while some 42% of farmers between the age of 55 and 64 said they had experienced suicide in the local community or among neighbours