John Whelan: Will Taoiseach’s trade mission prove a turning point for Irish exports to China?

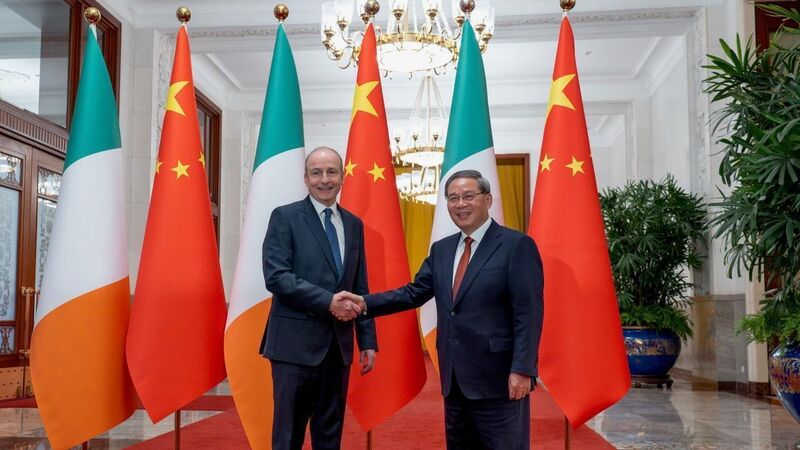

Taoiseach Micheál Martin shakes hands with Chinese premier Li Qiang in Bejing last week. Mr Martin made the case for Irish exporters including agrifood exporters. Picture: Government of Ireland/PA Wire

Despite high hopes, the recent visit of Taoiseach Micheál Martin to China may not be enough to halt the fall in exports to our largest market in Asia, as tensions continue to rise between the EU and China.

Ireland’s exports of goods to the Chinese market have been on a downward path for some years, falling by €3.8bn in the four years to December 2024. Based on Eurostat figures, they are expected to have fallen by a further 13% in the past year.