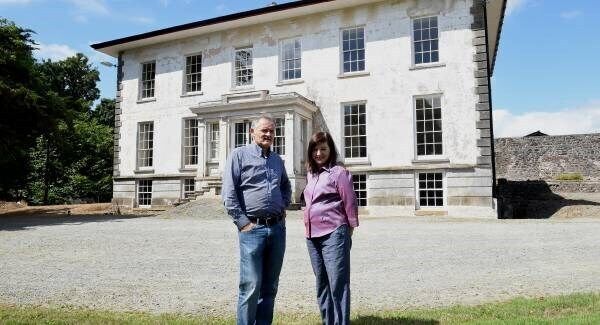

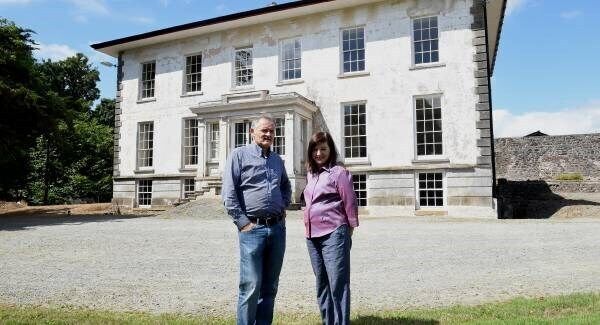

Love and Laurentinum: One couple's crusade to conserve an 18th Century manor house

Open for Heritage Week, visits a Georgian house in North Cork being restored on a shoe-string budget by its very committed owners.

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBEOpen for Heritage Week, Kya deLongchamps visits a Georgian house in North Cork being restored on a shoe-string budget by its very committed owners.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

Sign up for our weekly update on residential property and planning news as well the latest trends in homes and gardens.

Newsletter

Sign up for our weekly update on residential property and planning news as well the latest trends in homes and gardens.

Tuesday, February 17, 2026 - 10:00 PM

Tuesday, February 17, 2026 - 5:00 PM

Tuesday, February 17, 2026 - 10:00 PM

© Examiner Echo Group Limited