Monstrous shark ruled ancient Australian seas before megalodon, researchers say

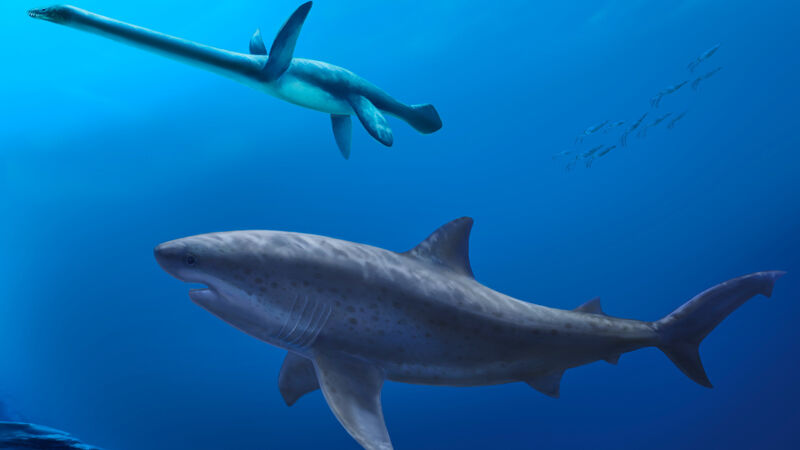

A illustration of a gigantic mega-predatory lamniform shark swimming beside a long-necked plesiosaur in the seas off Australia 115 million years ago (Pollyanna von Knorring/Swedish Museum of Natural History/AP)

In the age of dinosaurs, before whales, great whites or the bus-sized megalodon, a monstrous shark prowled the waters off what is now northern Australia, among the sea monsters of the Cretaceous period.

Researchers studying huge vertebrae discovered on a beach near the city of Darwin, say the creature is now the earliest known mega-predator of the modern shark lineage, living 15 million years earlier than enormous sharks found before.