Too small, too Cork - the rejection that fired up Roy Keane

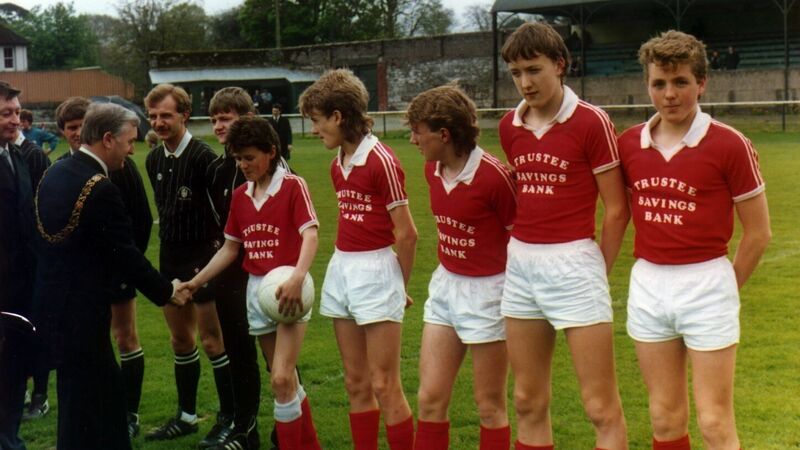

Cork Kennedy Cup captain Roy Keane meets the Lord Mayor Dan Wallace ahead of the Kennedy Cup final in Cork. Also in the picture are Len Downey and the late Paul McCarthy, both teammates of Roy's at Rockmount.

Focusing on the period between 1988 and 1993, ‘Keane: Origins’ charts the Corkman’s formative football years at home while examining his three seasons under Brian Clough at Nottingham Forest In the following extract, a teenage Keane experiences a litany of underage omissions with the Republic of Ireland, setting the tone for the tension that simmered much later on.