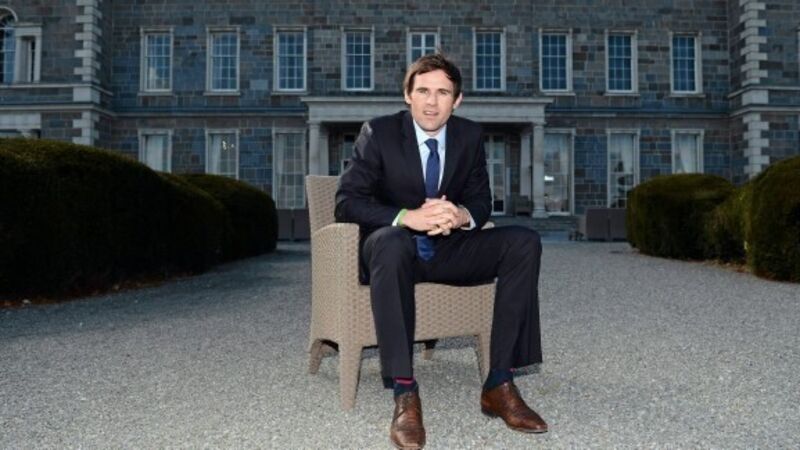

Kevin Kilbane: The ultimate professional

If you’re ever doubting why Kevin Kilbane is constantly on the airwaves and on trains, planes and automobiles all around Britain covering games, it’s because he’s seen just about everything in football.

He’s played in World Cups, yet started and finished in the lower leagues. He began in a dressing room where the most foreign player was Welsh but would later inhabit others where he’d take African team-mates to dinner and them unable to say a word to him. He’s seen so-called mind gurus come in and smash wood and walk on glass in front of his baffled team-mates and another who instructed them all to hug one another. He played with Wayne Rooney when the kid was 17 yet Rooney wasn’t even the best 17-year-old he came across — that would be Robbie Keane. He’s been a hero and a scapegoat to fans, ridiculed and abused by some and lauded, even loved, by others. Yet all that time he seemed to carry himself with a certain poise and dignity, underpinned by a resilience, that would prompt Mick McCarthy to hail him as a pro’s pro and about the most genuine man he’d met in football, someone “I’d be proud to have as a son”. If Kipling knew Kevin Kilbane, he’d probably describe him “as a man, my son”.