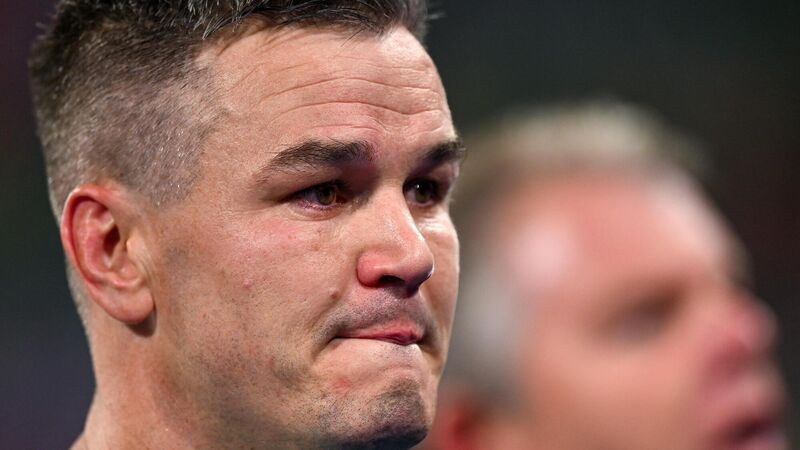

Not like this, please... Sexton heads forlornly for the hills as the end becomes a reality

PAIN: Jonathan Sexton after the cruel defeat at the Stade de France.

There’s a scene in The Matrix where Apoc is about to quite literally pull the plug on Switch and the rest of the team. Cypher, who can only stand there helplessly and look on as the inevitable happens, utters what everyone else is thinking. “Not like this,” she says. “Not like this.”

We were all Cypher here. Helpless. Horrified. Resigned.