Munich 1972: Witnesses to Olympic terror remember Munich horror

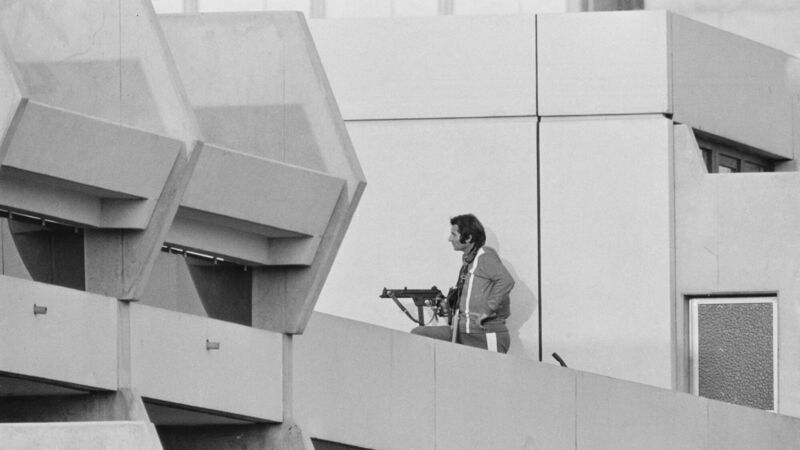

HORROR: An armed police officer maintains surveillance in the Athletes' Village during the 1972 Munich Olympic Games in Munich, West Germany, after Palestinian terrorist group Black September had taken hostages at the quarters of the Israeli athletes, 5th September 1972. Pic: McCabe/Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Fifty years. Hard to imagine. For Mike Sands, Donie Walsh and Phil Conway, there are certain memories of the 1972 Munich Olympics that have long been washed away, lost in the vault among all that happened over the last half-century.

But then, there are certain images, feelings, that will never leave them.