John L Sullivan: The son of Kerry who became America's first sporting icon

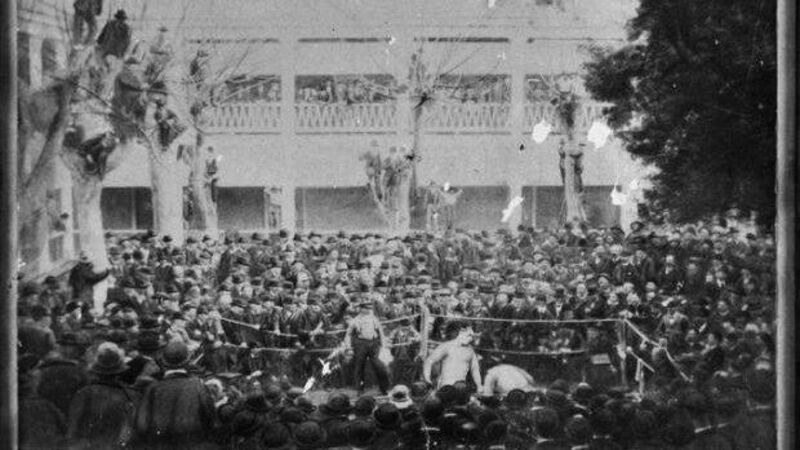

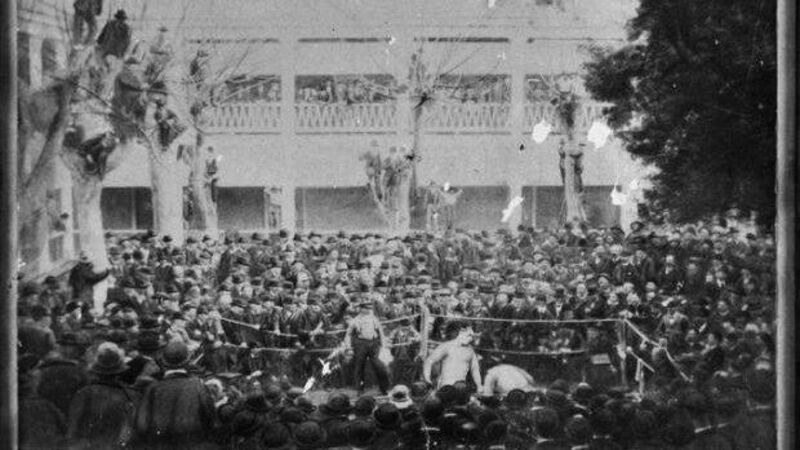

Paddy Ryan and John L Sullivan engaged in a clandestine prize-fight with the title of Champion of America at stake.

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBE

Paddy Ryan and John L Sullivan engaged in a clandestine prize-fight with the title of Champion of America at stake.

This is a weekend to take a step back in time, back to the town of Mississippi City in Harrison County, Mississippi where on February 7 1882, Paddy Ryan and John L Sullivan engaged in a clandestine prize-fight, an activity outlawed in all states of the USA, with the title of Champion of America at stake.

A prize-fighter in the eyes of the law was a professional criminal and practitioners occupied a place on the social spectrum occupied by labourers, saloon keepers, gamblers, criminals and prostitutes.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

Latest news from the world of sport, along with the best in opinion from our outstanding team of sports writers. and reporters

Newsletter

Latest news from the world of sport, along with the best in opinion from our outstanding team of sports writers. and reporters

Friday, February 13, 2026 - 10:00 PM

Friday, February 13, 2026 - 9:00 PM

Friday, February 13, 2026 - 10:00 PM

Select your favourite newsletters and get the best of Irish Examiner delivered to your inbox

© Examiner Echo Group Limited