Liam Griffin: Nickey Rackard did more for hurling in Wexford than anyone did for any county

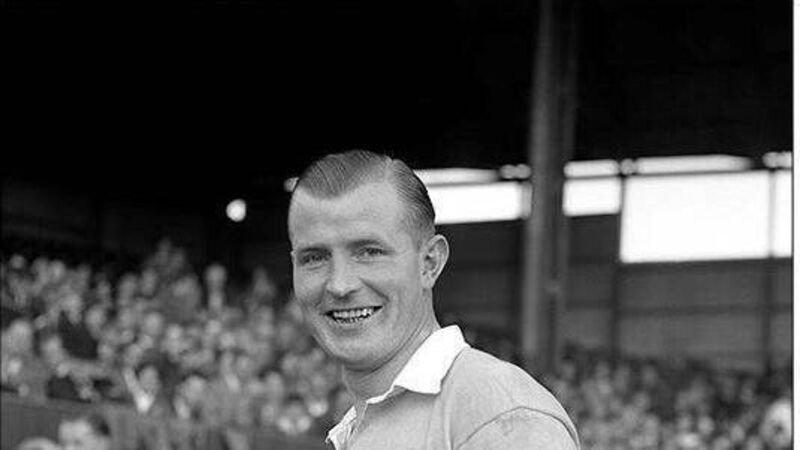

SHARPSHOOTER: 65 years after his retirement, Nickey Rackard remains the leading all-time championship goalscorer.

The hand that held the stick of ash

The man who led with style and dash,

Oh! Carrigtwohill once felt the crash

And Bennettsbridge and Thurles.

And when in later life you beat

The Devil, on that lonely street,

Then showed us how to take defeat

With dignity and courage.

The last parade was long and slow,

The last oration- spoken low,

And as on green fields long ago,

The ‘Diamond’ stood beside you.

Old comrades flanked you side by side,

The tears they shed were tears of pride,

An ash tree toppled when you died

And scattered seeds at random.

Poem by Tom Williams