MAKING THE GRADE

AFTER the Munster U21 semi-final win over Clare in 1964, I received another letter from Tipperary County Board, this time inviting me to train with the senior team.

Before my first training session we had played Waterford in that Munster U21 final where I sustained my broken wrist.

After just being called up to the Tipp senior panel, it was killing me not being able to join in fully. I couldn’t train as my wrist was in plaster up to my shoulder, but I still went to training and when the boys were gone out hurling, I togged out with my arm in a sling.

The minute the running part started, I ran out of the tunnel and into the group, and ran away with the lads.

Paddy Leahy was the head man that time.

“YOUNG GAYNOR!” he roared.

“YOUNG GAYNOR... COME BACK HERE!!”

I let on I didn’t hear him. I was pure eager to be there and be part of it. And Paddy didn’t say a thing to me afterwards.

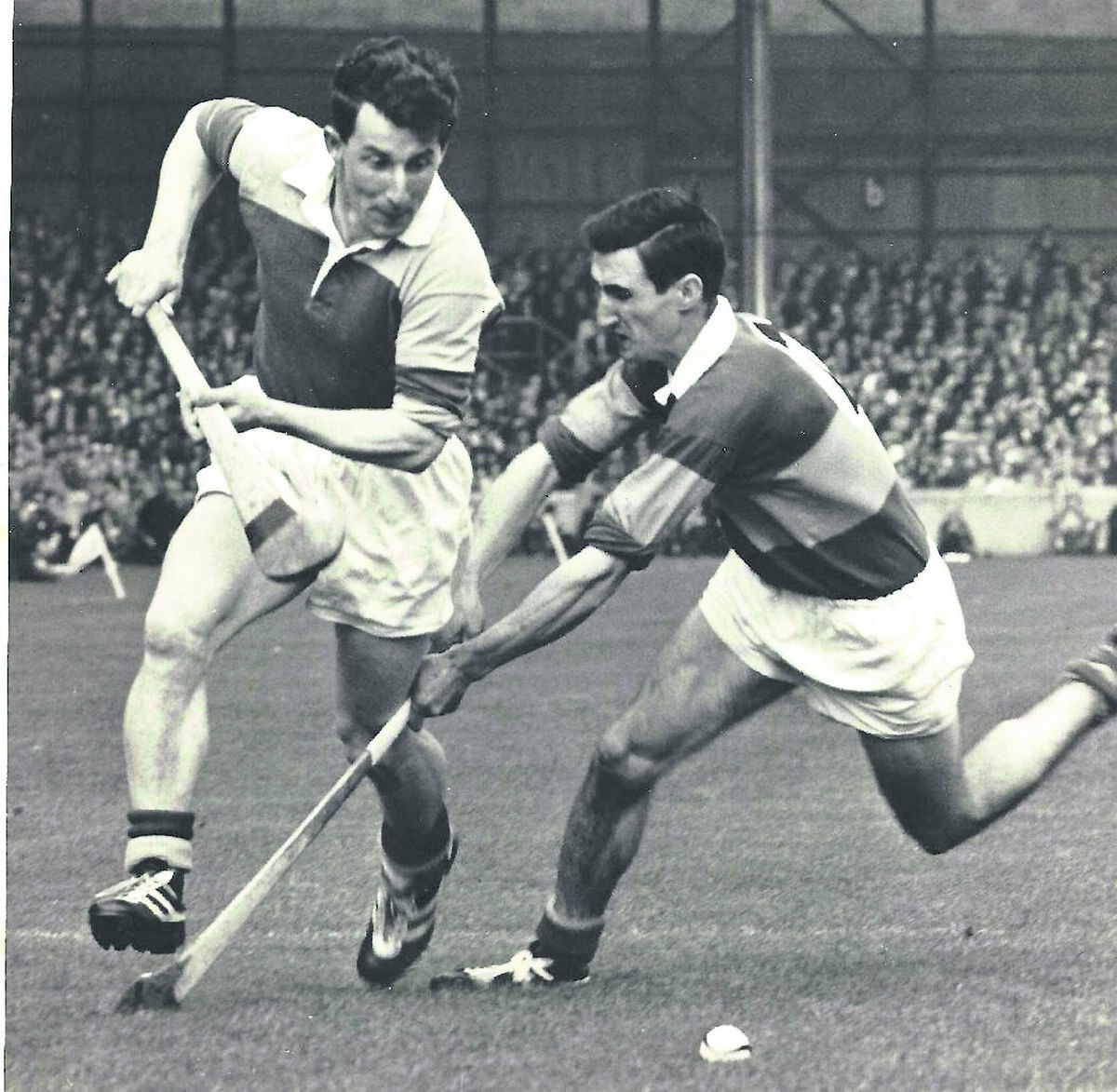

The first evening I could train properly in Thurles, there was a very tricky ball that stopped dead in the middle of the field, and I was coming out to the 45 to meet it. And Theo English was coming the other way. I said to myself... This is going to be a fair one!

Theo English was a very strong, powerful man. I never saw him on the ground, I don’t think anyone ever knocked him down.

Well, I went headlong into him and neither of us fell, and I got the ball away. I was thinking... This is tough... but I’m still alive.

I quickly learned how to survive.

We had great men around us such as John Doyle, Michael Maher, and Kieran Carey in the full-back line; they were powerful men.

They had a reputation for being rough, tough, and dirty and were given the immortal title of “Hell’s Kitchen” but they weren’t really. They were tough and used their power and their weight to their advantage. Doyle loved a skirmish and pounding into lads, and the Tipperary fans loved him for it.

We came in one day after playing Cork, and this elderly supporter was in the dressing-room. How he got in I don’t know. But there he was, rubbing down John Doyle. I was looking around wondering where my shirt was, and I saw it was my shirt and vest he was using to rub him down with.

John Doyle was royalty.

For us as backs, marking the likes of Jimmy Doyle, Mackey McKenna, Donie Nealon, Larry Kiely, and Liam Devaney, who were all powerful hurlers, was huge. We realised we could only get better by marking them every night in training.

When you’re watching those lads and seeing the things they could do, it would drive us on as well. I was raw enough going in there as a young fella. I might have been good at home in the club and thinking I had it all, but when I went to Thurles it was another step again.

The first job was to learn to survive.

It was pretty daunting starting out with that group of Tipperary seniors, who prior to my arrival were being touted as one of the greatest teams of all time. Not only were they a focused team that put the work in to be as good as they were, they were also a great group of friends who looked after each other and made each new arrival on to the panel feel part of the group right from the start.

On training nights, Mackey McKenna would do the driving as he started out the furthest north, in Borrisokane. Then we would head up to Newtown for Donie Nealon and back into Nenagh to pick up Mick Burns and then on to Borrisoleigh for Liam Devaney, until he got married and moved into Thurles. That was our load and we used to have right craic.

Liam King came on the panel later and he’d be coming from Lorrha and he used to bring us then. Mackey was a devil for the greyhounds. Himself and a man called Tom Brereton from Thurles had a greyhound between them and the deal was one of them had him for six months to keep, feed, and train, and then the other would have him for the next six.

Mackey had his term completed and it was his partner’s turn to take him, but he wouldn’t take him as the dog was no good. We brought the dog over in the car one evening with us to training and tied it to Tom’s door, and we went on to the field.

The next evening we went into training and when we came out the greyhound was tied to the door of Mackey’s car, and we had to bring him home again. He must have been a real dud of a greyhound.

When Liam Devaney was living at home in Borrisoleigh with his parents, they reared sows and they used to sell them for a fiver apiece. One evening, we called to Devaney’s house and there was no sign of him. We were after blowing the horn for a good few minutes.

Eventually he came out. “What the hell kept you?” Donie Nealon asked.

“The sow was having banbhs,” he said.

“You and your banbhs... we have an All-Ireland to win!”

“All-Ireland me eye,” said Devaney, “... and every fart a fiver”.

WE were coming home from Kilkenny after a league match, once, after we had been beaten. Myself, Mick Burns, Mackey McKenna, Kieran Carey, and Martin Kennedy were in Mackey’s car, but I was driving because I didn’t drink.

We stopped first in a pub in Urlingford. We moved on then and the boys were all asleep in the car when we got to Young’s of Latteragh, a few miles from Nenagh. They had a pub and petrol pumps.

All of a shot, Mackey woke up and said: “Pull in... pull in, we need petrol”. I pulled in and the doors shot open and the boys headed for the pub.

We got inside and there were a good few still there. I was livid because I was hoping to get into Nenagh for the last dance in the Ormond Hotel.

I wasn’t even drinking water; I was sick after drinking minerals in Urlingford.

We weren’t long there, when in came the Gardaí and raided the place. We were asked for our names and the first man gave a wrong name. Then Martin Kennedy was asked for his name.

“John Shea,” says Martin.

I heard this and I thought... We are going to go to jail. “Where are you from John?” asked the guard.

“Ballycommon,” said Martin.

“Ballycommon where?”

“Ballycommon, Nenagh... where do you think?” said Martin.

The next thing, Mick Burns gave me a dig in the ribs and told me to give him my right name. I felt a massive relief, hearing that, and so we all gave our names. Some lads got out of the place through a little tiny window and Mackey McKenna saw them. You wouldn’t get an eel out through it, he told us. But still a couple of lads went out through it.

We were all fined two pounds each in Nenagh Court a while later for being found on the premises after hours. It managed to make the Evening Press newspaper later in the week with the headline... “Tipperary stars drown their sorrows after hours.”

At the end of 1964, Tipperary got to the All-Ireland final and there were 24 players on the panel, but Croke Park sent word that there would be only 20 medals.

Four lads had to be dropped.

Thankfully, I kept my place.

I often think back that maybe the selection committee were impressed when I did my training when I was injured. I didn’t do it for that reason, but something clicked with the manager that they kept me on, and the other lads were dropped. I was an unused sub as Tipp beat Kilkenny in that final.

A few weeks later, we were playing

Kilkenny again in the Oireachtas final at Croke Park. There was a big crowd there, around 50,000.

The All-Ireland team was picked to start again, and I was still a sub.

When we got to Croke Park, Mick Burns couldn’t play; he was injured, so I was told in the dressing-room that I was playing.

Séan McLoughlin was a great leader at that time. He caught me by the front of the jersey and pinned me up against the wall. “You’re going to be marking Eddie Keher today!” he told me.

“Oh right,” says I.

“You know,” he says. “If you stop him from scoring, we’ll win this match. Do you hear me?”

“I do!” I told him.

I knew it was serious then.

I would have known a bit about Eddie Keher because he was on the St Kieran’s College team that beat St Flannan’s in an All-Ireland Colleges final in 1957.

I had seen him play with Kilkenny and knew he was good. I got stuck into him good and tight and didn’t give him many chances. I don’t know what he scored; but he scored some of the frees anyway. He was a great free-taker.

I didn’t play well that day as I was a little anxious, and the minute I saw the ball I was pulling on it to get rid of it. Tony Wall was telling me to pick it up. I didn’t think you’d be allowed to pick it up in county hurling.

I took a lineball under the Hogan Stand in the first half. We were down 11 points and wave after wave of Kilkenny attacks were coming at us. I took the lineball and I got a great connection and it landed into the square, and into the net it went.

It wouldn’t have gone into the net only for Séan McLoughlin, who did a war dance in front of the goals, with the ball going in between his legs and then between Ollie Walsh’s legs and into the net. The goal was credited to Séan McLoughlin on the paper the next day and I was a bit disappointed.

Paddy Leahy came up to me at half-time. “Good man young Gaynor... that was a great goal.”

That gave me a lift and I never forgot it.

It was about the first and only time I got a bit of praise. I don’t ever remember getting any other praise. I really didn’t play that well, I thought. I was wired anyway to stop Eddie Keher from scoring so I wouldn’t be killed in the dressing-room.

At half-time, I thought there would be changes and I would be taken off. There wasn’t a word said however and next thing, Theo English stood up. “Boys... it’s time we got down to business and beat these fellas.” And beat them, we did.

That’s all it took to spark us. That team knew they had it in them. Nobody had to beat the table or pound the door; it was as simple as that.

I never forgot that because it was a huge message about keeping calm when things are going wrong. There was no one effing anyone else out of it. One man would tell the next man to his face if he did something wrong or didn’t hit the ball right.

WE usually trained two nights a week and if we got to an All-Ireland it would be upped to three.

It was generally Tuesdays and Fridays, and we’d hurl away. There’d be a match straight away.

I could be on Jimmy Doyle one night or Donie Nealon another... Mackey McKenna, Larry Kiely... whoever you were on you were playing against the best. Then we’d do a few rounds of the field; then we’d do a few sprints, and that was it.

Ossie Bennett was the trainer. He was good in fairness. He was a powerful man; he drove us, and he’d drive you for that last bit of a sprint to get the most out of you.

It was completely different to nowadays.

There wasn’t a lot of emphasis on training really. They would be advising you to mind yourself and eat the right stuff... whatever that was. They’d tell us to keep away from the drink.

We got good advice. We would be told how to carry ourselves as well. Maybe people would notice if lads were in a pub and having a pint, and even back then that number of pints would reach 10 by the time the story would end in different parts of the county. So, no different to now on that front, lads did have to mind themselves.

I wasn’t a drinker at all, I didn’t drink

alcohol.

I wouldn’t have had a routine, but I would make sure to keep occupied. There were a lot of farmers hurling at that time. If you went forking bales or something like that, which you might not be used to doing, you’d be murdered the next day.

But I believed that I should keep myself busy at something that I was comfortable at, whether that was out in the garden digging spuds, or something easy like that. Or painting a door... I always wanted to keep myself occupied.

There’s a story about Tony Wall, who was living in Cork at one time, when he was in the army. He had a next-door neighbour who was a big Cork supporter. Cork were going through a lean time in the 60s and this man would always feel the next year would be Cork’s year. He was good friends with Tony.

Anyway, it was the 1965 Munster final between Tipp and Cork, and your man was high all day on the Saturday that they were going to beat Tipperary the next day. All day he was at it, but in the evening he went out the back door to his garden to put in a bit of time. He looked over the fence and there was Tony Wall with a mac on him, a cap and a wheelbarrow and he working away in his garden. The man couldn’t believe it and he went back in and sat down, and said to the wife: “We are bet.”

And they were beaten well the next day. He couldn’t believe Tony was so calm and collected the day before a Munster final.

I admired all the players on the squad, many of whom had won All Irelands in 1961, ’62, and then ’64 when I came on to the panel. Tony Wall was my real favourite, however.

I read about him in 1958 when he was hurler of the year. I liked him because of the way he played and how good he was, and how he had improved himself. When he first got on the Tipperary team, they played him wing-forward and centrefield, and eventually they dropped him into centre-back which he made his own and he stayed there for years.

He was very good to me when I went in and when I was playing beside him. He’d be encouraging me all the way; he’d never say a wrong word.

Just pure encouragement all the time.

THE boss, Paddy Leahy didn’t say much but when he spoke, we listened.

In that first campaign with the U21s, Paddy was brought into the dressing-room before the first match against Cork.

One of the selectors said: ‘This is Paddy Leahy... manager of the Tipperary senior team’.

I had heard of him but had never seen him before.

His words were magical. “Boys, we are the Premier County. So we want to win this first All-Ireland in U21 hurling to keep our reputation as the Premier County.”

That was it and off he went.

Paddy was a very sound man. He’d speak at the last training session before a match and he would tell you what was expected of the team and different individuals, not much generally, but what the backs had to do to keep the forwards out, and for the forwards to take their chances.

He knew all about each of us. He knew if we stepped out of line, and he would let us know about it. You wouldn’t last on the panel if it was anyway serious at all, you’d be gone! He knew his hurling. He was able to make all the important moves during a game, to change the flow of a game.

We trusted him and we believed in him.

He had been through it. He had been a great hurler himself having won two All-Irelands in the early decades of the century.

He didn’t have the title of manager; he was chairman of the selection committee. But he was the man and we all knew he had done it before. He was there from 1949 when Tipperary’s golden era began, right up to ’65 when he was forced to step away due to ill health, and in that time, there was never any doubt about who was in charge.

There was never any talk of him going or being removed. There was never any question that he was going to be the man again. There might be a change in the selectors but not Paddy Leahy, he was consistent.

I admired him and I would take everything he said seriously. He was a great leader, but the dressing-room was really full of leaders.

Tony Wall was a great leader, a very wise man.

Theo English was a leader.

Séan McLoughlin was a big leader. If you ballooned a ball over McLoughlin’s head he wouldn’t be long in letting you know about it. Doyle, Maher, Carey... they were leaders in their own right without saying too much.

One day before my first All-Ireland final in 1965 we were out on the field, pucking around and I remember asking Mick Maher: “What will I do today?” I thought maybe that playing in the All-Ireland final there was something extra wanted.

“Play the game as normal,” he told me. “Get the ball and hit it... keep it simple.”

After the Oireachtas final in 1964, I was on the senior team after that for good. I never lost my place until I retired in 1974.

By the time the National League came around in 1965, Mick Murphy had injured his knee, which finished his career, and I got to play left wing back and I stayed in the No. 7 jersey for nearly the next 10 years.

Seeing Mick finish so young was cruel. It’s only now I realise it was a cruciate ligament injury that finished him, as they couldn’t do anything about it at that time. I used to hear the boys saying that Murphy was playing great, but they believed that I was ready to take his place.

The Len Gaynor autobiography, Chiselled from Ash, is published by Hero Books (print €20.00/ebook €9.99) and is available in all good book shops and online at Amazon, Apple, and all digital stores.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates