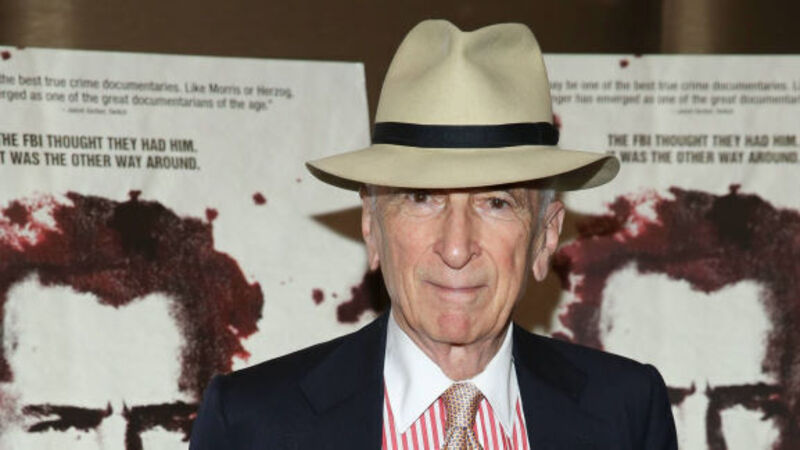

Living proof style never goes out of fashion

“You’re from Cork?” says Gay Talese. “I know Cork. That’s where my wife’s family comes from.”

With that Talese is off and away.

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBE“You’re from Cork?” says Gay Talese. “I know Cork. That’s where my wife’s family comes from.”

With that Talese is off and away.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

Latest news from the world of sport, along with the best in opinion from our outstanding team of sports writers. and reporters

Monday, February 9, 2026 - 5:00 PM

Monday, February 9, 2026 - 7:00 PM

Monday, February 9, 2026 - 8:00 PM

© Examiner Echo Group Limited