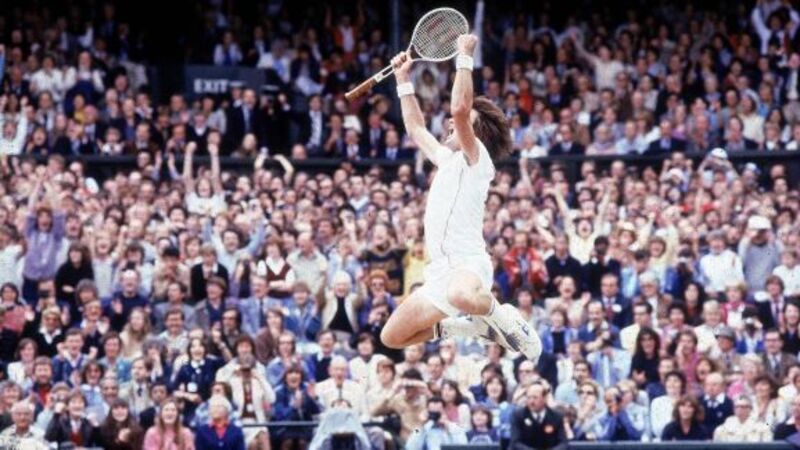

Always an outsider, always a winner

There’s no denying Jimmy Connors’s victories are some of the most enduring memories of tennis.

Yet there’s also no denying the era in which he claimed these victories has faded. The technology of court surfaces and rackets has changed the game he knew in the 1980s almost beyond recognition.