Kieran Shannon: Nothing like that winning feeling for Mayo

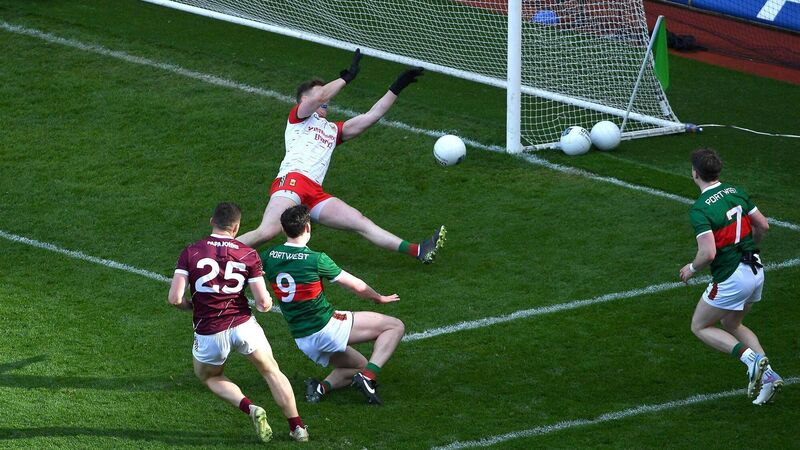

CLEAN SHEET: Damien Comer of Galway has his shot on goal saved by Mayo goalkeeper Colm Reape during the Allianz Football League Division 1 final at Croke Park in Dublin. Pic: Tyler Miller/Sportsfile

For the last time a team won the Sam Maguire having lost a championship game at some stage along the way, you have to go back 12 whole years, as it happens the first summer in a decade and a half that Ciarán Whelan wasn’t suiting up for Dublin.

Instead he spent that championship of 2010 in the stands, either as a punter or a pundit, watching Dublin come storming through the backdoor only for Cork, another side who had availed of the qualifiers, pip them in the All Ireland semi-final before going on to win it all.