Tommy Martin: Páidí's enormous presence endures in in the thousands of stories

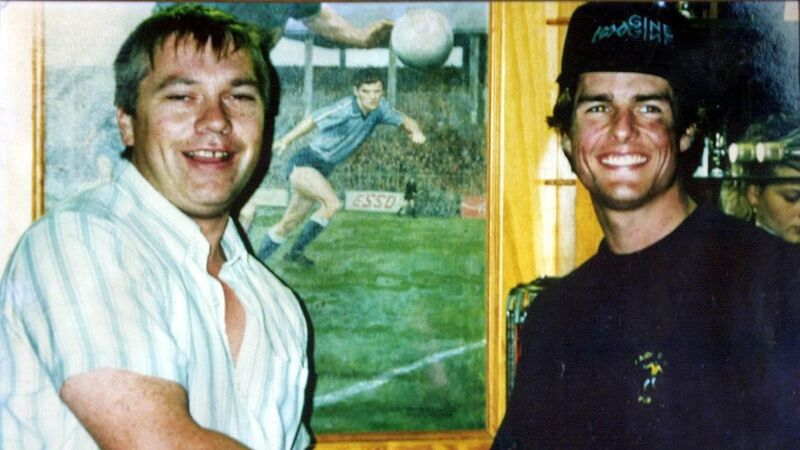

SUPERSTARS: Tom Cruise is welcomed by Páidí Ó Sé to his pub in Ventry Co. Kerry. Picture supplied by Don MacMonagle

It’s March 2008 and Páidí Ó Sé is in Dublin to launch his annual football competition. It is an invitational club tournament that takes place in the Kerry Gaeltacht, so naturally you launch it in the ballroom of the Shelbourne Hotel. Or at least, you do if you are Páidí.

Into the room in a cluster of handlers and reporters sweeps An Taoiseach himself, Bertie Ahern. Embattled and on the brink, all eyes are drawn to him. His finances and those of the country are the topic of the day. The Mahon Tribunal is in full flow. A week earlier he’d been described in Dáil Éireann as a “national embarrassment”. He is not long for this realm.