John Riordan: NBA icon Bill Russell changed the game and changed society

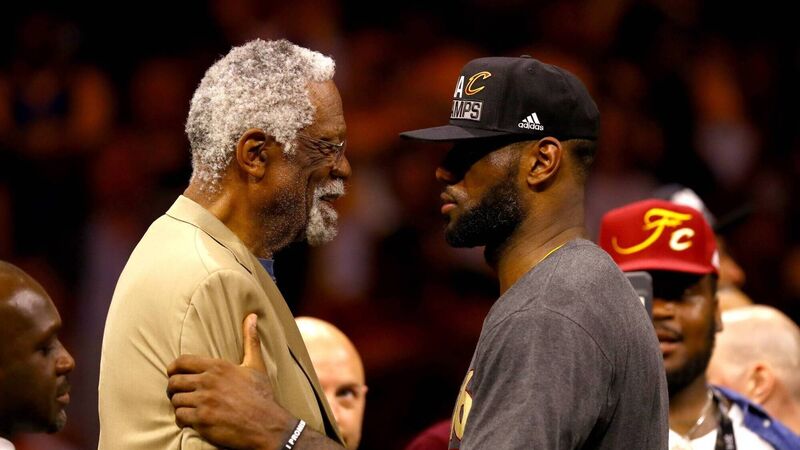

MVP: Bill Russell with LeBron James after James was named NBA Finals Most Valuable Player in 2016 (Photo by Ezra Shaw/Getty Images)

This sporting week began on a sad note as America and the world of basketball mourned the loss at 88 of all-time Boston Celtics and NBA icon, Bill Russell.

And it will conclude on a slightly awkward note that he would have chuckled at; over the next few days, Premier League players are tapering off their first-whistle ritual of bending one knee before games begin.