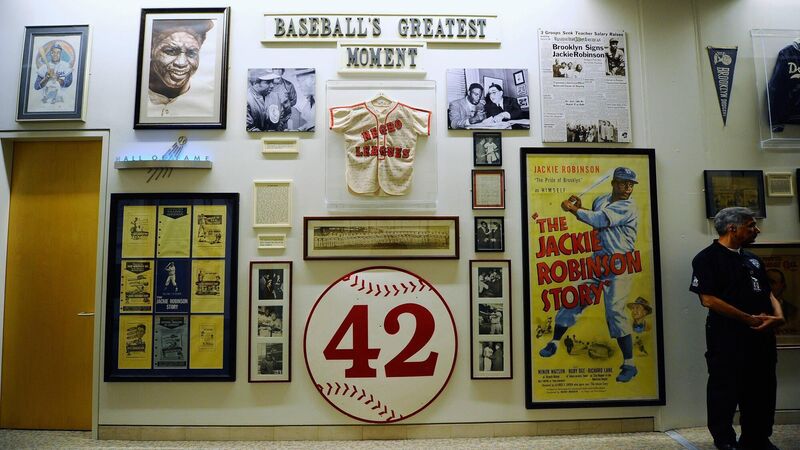

John Riordan: Brooklyn and the US unite for Jackie Robinson Day

75 years ago today, Jackie Robinson wore 42 for the Brooklyn Dodgers at Ebbets Field for the first time, becoming the first Black man to play in a league that had up until then segregated players of African descent away from its ballparks.

The number 42 holds special significance in the history of the GAA and, even more significantly, in the history of Major League Baseball.

Rule 42 was amended almost 20 years ago and paved the way for the unforgettable Six Nations visit of England to Croke Park in early 2007. Although it was a movement of wording and wrangling and hand wringing, it ultimately represented an opening out of attitudes and a break from the past.