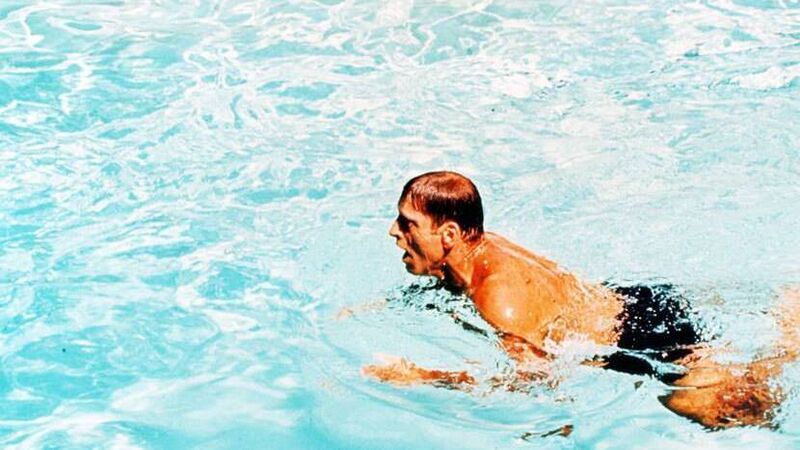

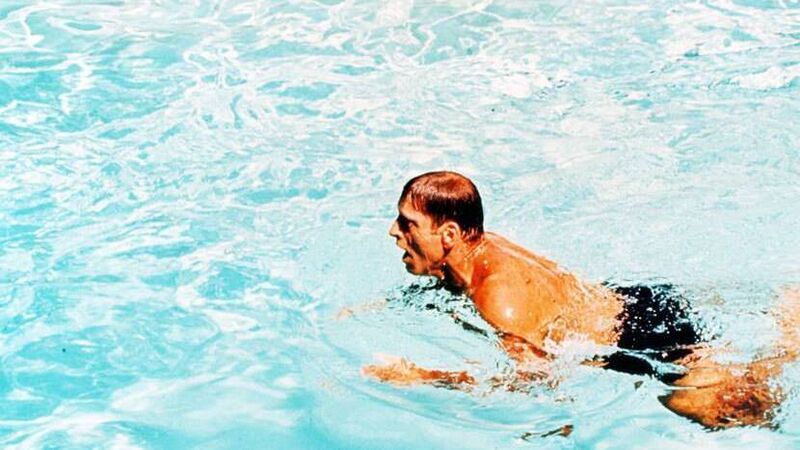

Paul Rouse: ‘The Swimmer’ still stands the test of time

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBE

Burt Lancaster in The Swimmer (dir. Frank Perry, 1968). The story is a stunning feat of imagination, utterly original.Picture: Columbia Pictures/Photofest

There are some brilliant short stories related to sport, collected in various volumes and perfect for holiday reading. These stories run throughout the history of modern sports and include some of the most famous authors ever to publish works of fiction.

There is John Updike’s description of a baseball player trying to work out the reasons for his disastrous hitting problems in The Slump. And there is an entirely different type of short story in Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Croxley Master.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

Newsletter

Latest news from the world of sport, along with the best in opinion from our outstanding team of sports writers. and reporters

Newsletter

Latest news from the world of sport, along with the best in opinion from our outstanding team of sports writers. and reporters

Tuesday, February 10, 2026 - 12:00 PM

Tuesday, February 10, 2026 - 10:00 AM

Tuesday, February 10, 2026 - 12:00 PM

© Examiner Echo Group Limited