Eimear Ryan: Can a press conference really get to the heart of sport?

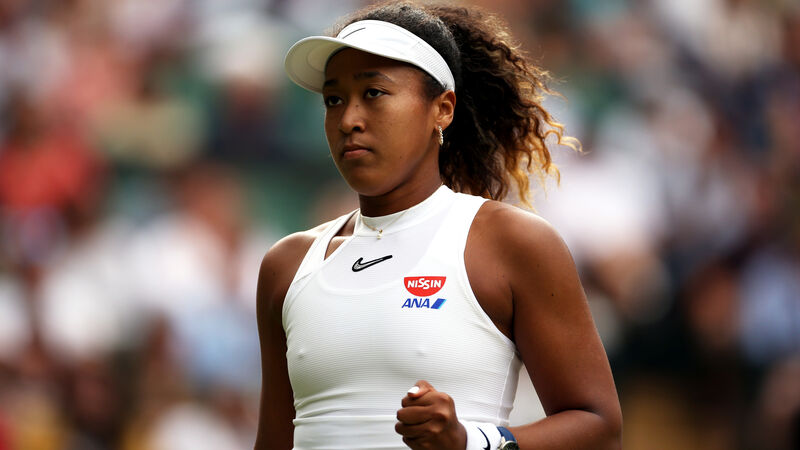

Naomi Osaka.

Is it just me, or have we had an unusually spicy national league so far? The action on the field has been entertaining enough, but it also seems that a lot of rivalries have played out in post-match managerial comment.

Whether it was John Kiely’s remarks about Galway simulation (which, in fairness to him, he swiftly apologised for), or the close-contacts issue escalating the ongoing frosty relations between Davy Fitz and Brian Lohan, there has been a fair amount of politicking on the sidelines.

After Wexford’s loss to Kilkenny on Sunday, Davy Fitz tried to call a halt to the media’s probing into an obviously newsworthy story. “The fact that ye make so much out of it is pretty unreal but I suppose ye have to do your job,” he told RTÉ’s Sunday Sport. “Ye’ve got to stop. We’ve got to get back to just hurling.”

Of course, in trying to shut down the story, Davy just gave it new legs. In this sense, he’s his own worst enemy, in that he is simply incapable of giving a boring interview. His emotions are palpable in his facial expressions and body language; his turn of phrase colourful. Have you tried not being such a tremendous character, Davy? Look at Cody, Father Stone-like in his stoicism, perpetually refusing to get excited about literally the most exciting sport in the world.

As stressful as I’m sure it sometimes is, speaking to the media does fall under a manager’s remit. In a way, a manager functions as a buffer and a communicator for his or her players, especially in difficult moments such as after a loss. In a week when sportspeople’s relationship with the media has come under scrutiny, it’s been interesting to reflect on what we expect from athletes — both professional and amateur, individuals or team players — once they step off the pitch.

The relationship between sportspeople and the media has always been a complicated one — not oppositional, as such, but certainly not as cosy as some press conferences make it out. There are different priorities on both sides.

A focused athlete, like a good politician, knows not to say anything much outside of the menu of safe, acceptable truisms and cliches — acknowledging their support system, respecting their opponents, complimenting the lads further out the field who deliver in such good ball.

The journalist, seeking an original angle or probing question, is longing for them to say something new or novel. Meanwhile, the athlete’s goal is to get out of the interview without distracting themselves or giving a hostage to fortune, some nugget that an opponent might use as motivation.

Up until a couple of days ago, I hadn’t realised that tennis players are obligated to participate in press conferences at major tournaments — not until Naomi Osaka pointed it out on social media. When the world no. 2 announced her intent not to do any press at the French Open, she signed off: “Anyways, I hope the considerable amount I get fined for this will go towards a mental health charity.”

It turns out doing pressers is mandatory, punishable by a fine. Which in a way, when you’re dealing with millionaires, is fairly meaningless; if anyone is well-placed to absorb an unexpected cost, it’s a world-class professional athlete. The true intent of the fine, I suspect, is to enshrine the press conference as part of the status quo, or even the rules of playing tennis at this level: if you’re not willing to comply, there’s a literal price to pay.

Osaka’s reason for her decision to not speak to the media was that it is hard on players’ mental health: “I’ve watched many clips of athletes breaking down after a loss in the press room and I know you have as well.”

When you put it like that, it does seem harsh that a tennis player — or a golfer, or runner, or any other elite individual sportsperson — would have to process and give an account of their performance moments after losing.

Some might argue that it’s part of the job, that you have to take the rough with the smooth, but we don’t do this in other industries. While Oscars coverage often encapsulates winners, losers, fashion, and winners and losers in fashion, it’s usually only the winners who are obligated to face the press pool.

Osaka’s complicated stand didn’t end well. Threatened with a ban and accused of diva behaviour and a lack of professionalism from certain quarters, she bowed out of the Open on her own terms to avoid becoming a distraction from the competition itself. In another post, she revealed: “I am not a natural public speaker and get huge waves of anxiety before I speak to the world’s media.”

Some sportspeople are brilliant at press conferences — charming, at ease, basking in the spotlight. But if you’re any way introverted, as Osaka is, I can imagine that press conferences can be nerve-wracking, anxiety-inducing, and draining — feelings which are definitely not conducive to performing at the highest level.

Athletes are athletes; they’re there to play. Are we asking too much of them, wanting them to be charismatic media personalities too?

It’s not that Osaka isn’t a highly effective communicator. She is — whether on social media, posting statements via her Notes app, or via the masks she wore at last year’s US Open to highlight the names of black victims of police brutality. But not everyone communicates in the same way. Some people are great at speaking off the cuff; others cling to their cue cards. Some people relish the chance to express themselves in writing; others don’t know where to begin.

And perhaps there are limits to the traditional press conference as a means of getting to the heart of sport. If you ask a sportsperson to describe how they felt at a particular moment when they pulled off some feat, they will usually describe it as a blur: they’re in a flow state, operating out of pure instinct, their mind blank.

If writing about music has famously been likened to dancing about architecture, writing about sport is similarly challenging — you can approach it, embellish it, translate it in a way, but never quite represent it fully.

If sportspeople invent their own ways of communicating their experience, let’s be open and receptive to new ways of listening.