Kieran Shannon: Game recognising game - when Prince met Muhammad Ali

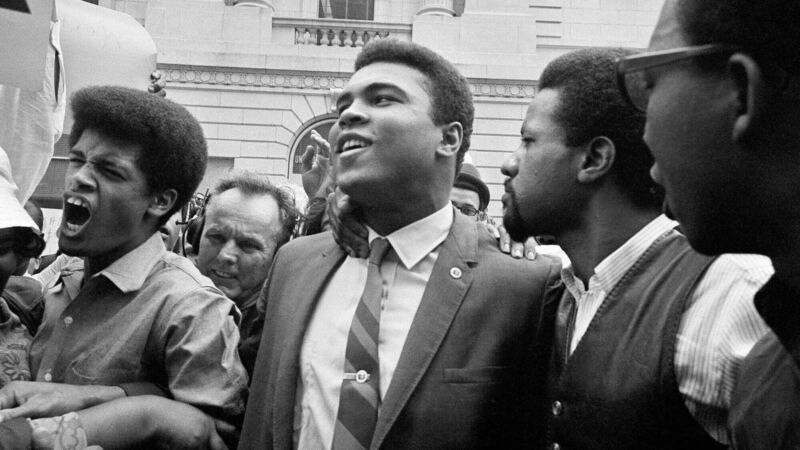

Muhammad Ali, center, leaving the Armed Forces Induction Center in Houston, with his entourage, after refusing to be drafted. Picture: Associated Press

Sightseeing was not something the artist known as Prince was into, for all the touring he did before he left this world five years ago this week, but one afternoon in 2007, out of obligation to his childhood hero, he made an exception: to visit a greasy old cemetery in Las Vegas where Sonny Liston had been buried.