Kieran Shannon: The Irish Whales who became the Olympic kings of old New York

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBE

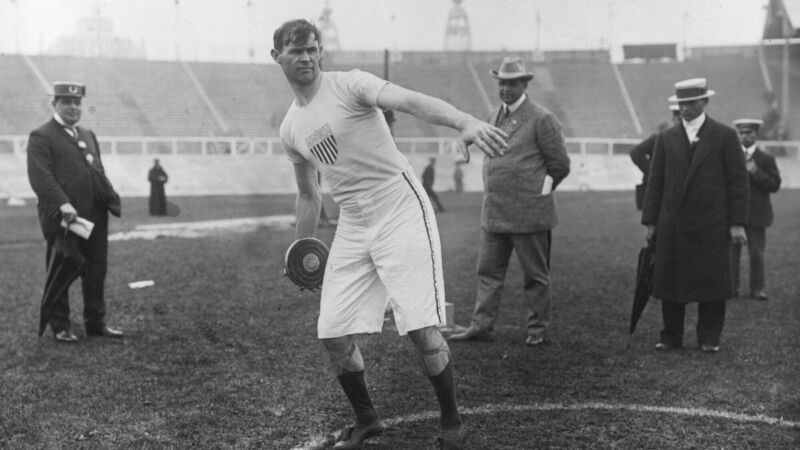

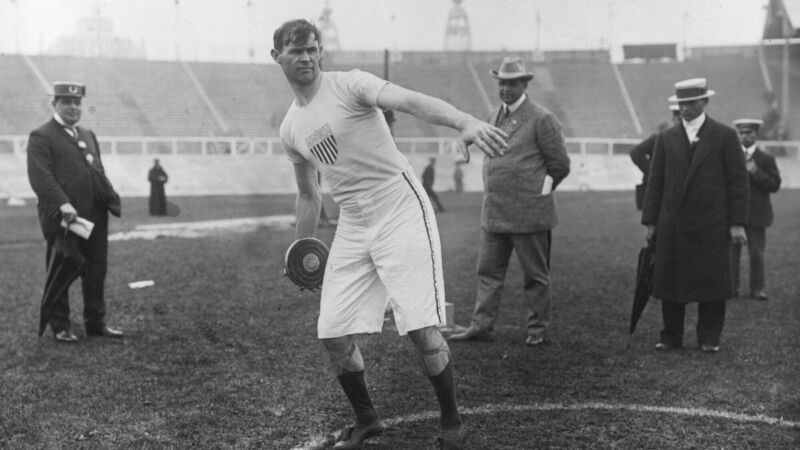

Martin Sheridan’s rightful place in history has been welcomingly preserved, or at least restored, but he was merely one in a line of exceptional Irish athletes at the time. Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

North Texas, February 1870 Kidd [Tom Hanks]: Good evening, ladies and gentlemen! My name is Captain Jefferson Kyle Kidd and I’m here tonight to bring y’all the news from across this great world of ours. Now I know how life is in these parts — working your trade, sun up to sun down. No time for reading newspapers, right? … So let me do that work for you. And maybe just for tonight, we can escape our troubles and hear of the great changes a’happening out there.

- ‘News of the World’, directed and written by Paul Greengrass (2020)

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

Newsletter

Latest news from the world of sport, along with the best in opinion from our outstanding team of sports writers. and reporters

Newsletter

Latest news from the world of sport, along with the best in opinion from our outstanding team of sports writers. and reporters

Monday, February 9, 2026 - 10:00 PM

Monday, February 9, 2026 - 9:00 PM

Monday, February 9, 2026 - 5:00 PM

© Examiner Echo Group Limited