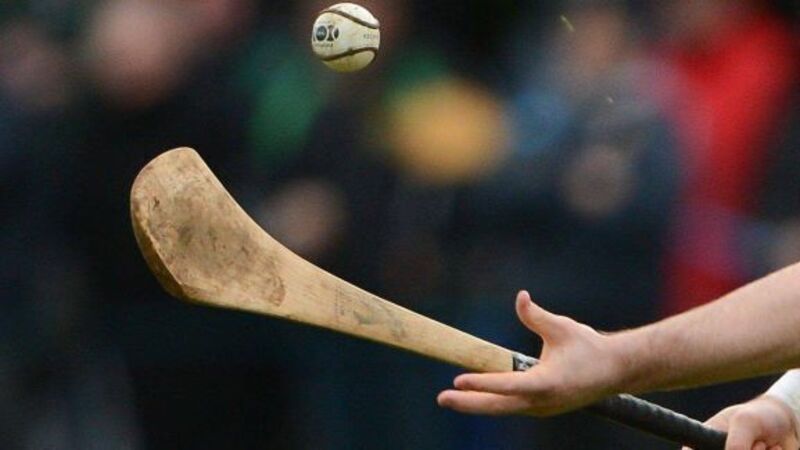

'The Hurley Maker’s Son' reveals how hurling is embedded in rhythm of life for some

He was felling the final tree of a day’s work in a forest near Athlone when the upper part lurched and hit him on the temple.

He collapsed bleeding into the sawdust on the ground. Two of his sons were working with him. They ran for help. The owner of the wood sought to revive him, but couldn’t.