The bottle and the damage done

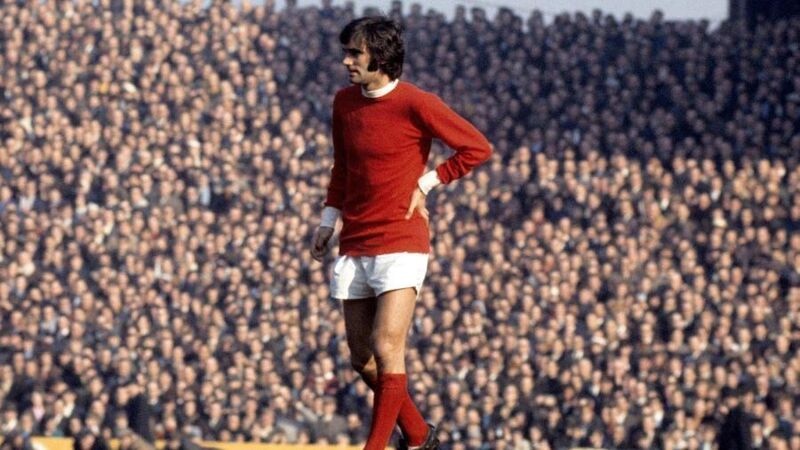

I reckon that must be close to one book for every one of those 50 years which may be why, in doffing a cap to the incomparable Georgie this week, I found myself happier to wallow in pictures rather than print.

Also marking that half-century anniversary, The Best Of Best — The Lost Images Of A Football Genius is in the magazine racks now and will, I promise, take your breath away. Of course, it helps if, like me, you were football-aware for at least some of the period covered, from that first appearance in ’63 through to the end of the decade. For here are colour and black and white images of huge evocative power: Best turning Bobby Moore inside out; exchanging a wary glance with ‘Chopper’ Harris; being hugged to within an inch of his life by Denis Law after scoring against Burnley at an impossibly packed Turf Moor; and, of course, drifting around the Benfica keeper under the Wembley lights to help Matt Busby realise his dream as United were crowned champions of Europe in 1968.