Think a bad call is tragic? Try having to retire at 25

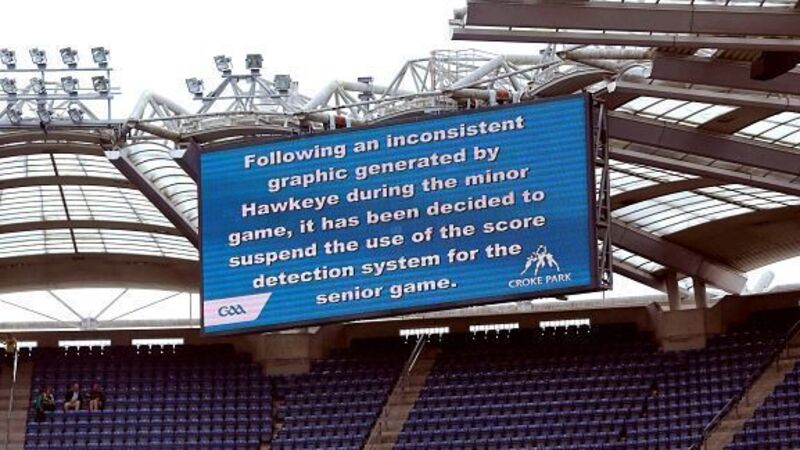

For Croke Park early last Sunday afternoon read Stamford Bridge on Wednesday night. Both stadiums witnessed obvious miscarriages of justice: Limerick’s minor hurlers denied a point by Hawk-Eye’s malfunction and Aston Villa sent back to the midlands without a point by Chelsea thanks to a pair of awful decisions which owed nothing to the whims of technology.

The ripples left in the wake of both games have been visible all week with the Limerick County Board and Villa manager Paul Lambert enjoined by an understandable sense of misfortune at events that undid what were commendable efforts by their teams to claim victory in contests of considerable import for both.