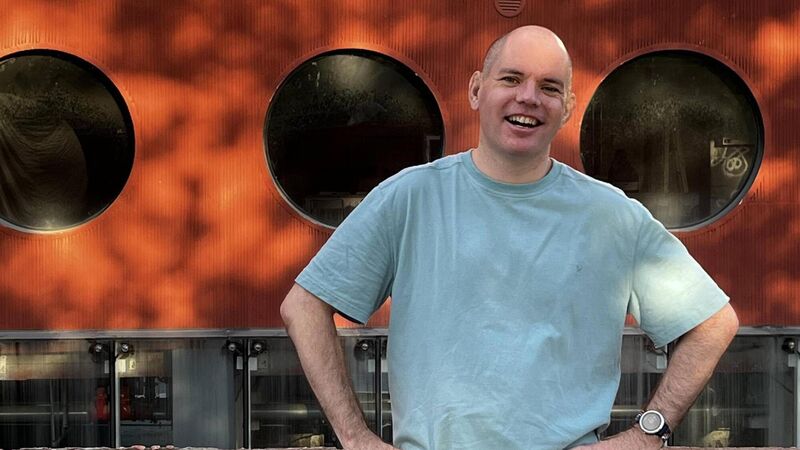

Richard Doran, loving life in the Beijing media spotlight

Richard Doran, a popular personality and occasional stand-up comedian on Chinese television and radio.

As a foreigner with a front row seat for the modernisation of China and its development as an economic superpower, Richard Doran has seen a lot in his two decades living in the Red Dragon.

Add in a varied and fulfilling media career, and the Irish television and radio host freely admits his time spent in the country has given him unexpected opportunities, despite the initial culture shock when he first arrived back in 1998.