In tune with nature: A singing bird is either at war or in love

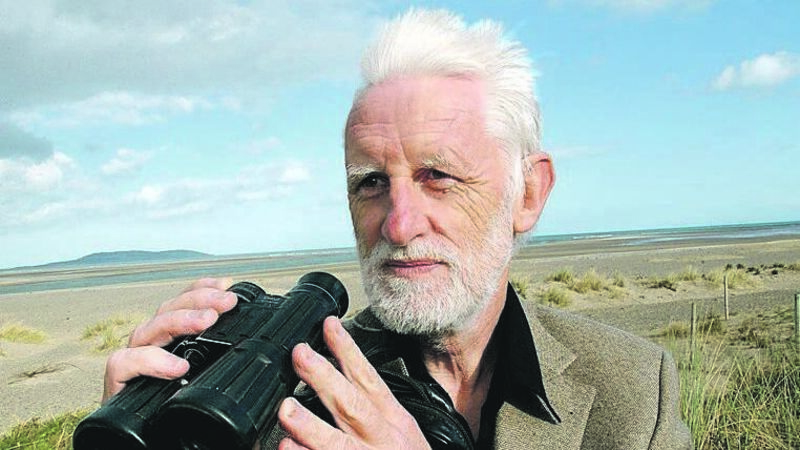

Richard Collins: 'Whales and birds are the wild world's great vocal communicators.'

Schoolboys 'take off' their teachers, exaggerating linguistic foibles mercilessly. Gillian Anderson, playing Margaret Thatcher in , gives The Iron Lady similar treatment. Nor is the ability to recognise vocal sounds confined to humans. When Rico, a border collie living in Dortmund, was just a few months old he began fetching items on hearing them named. By the age of nine, his owners claimed, he had memorised over 200 words.

Psychologists from the Max Planck Institute, in Leipzig, put Rico through his paces. He could, indeed, they found, recognise the names of over 200 objects. On average, he retrieved 37 of 40 items on command, a performance comparable to language-trained parrots and primates.