Donal Hickey: The story of the mysterious salmon is as old as time

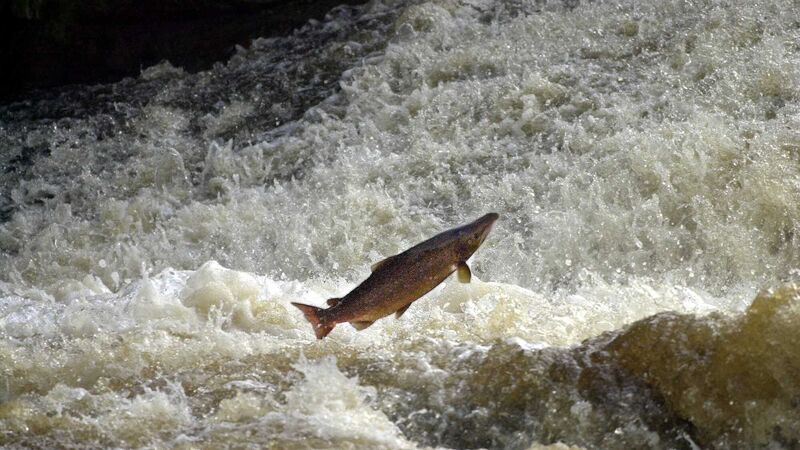

Salmon jumping over the weir on the river Blackwater in Fermoy.

If you walk along a riverbank these days you just might be lucky to witness a wonderful spectacle. It’s all about something which starts life as a pea-sized egg and later heads off to the wild Atlantic.

In the ocean, it can travel for thousands of kilometres before eventually returning as a fully-grown fish to the exact place of its birth. Everyone loves to see wild salmon leaping over various obstacles such as waterfalls and weirs as they come back to spawn.