Richard Collins: Alpha males show lead in the pencil

In his book, Darwin’s Island, geneticist Steve Jones claims that ‘Turlough O’Donnell, who died in 1423, had 18 sons and 59 grandsons’. "A fifth of the men of northwest Ireland share a more or less identical version of the Y chromosome, which means that they all trace ancestry from the same male".

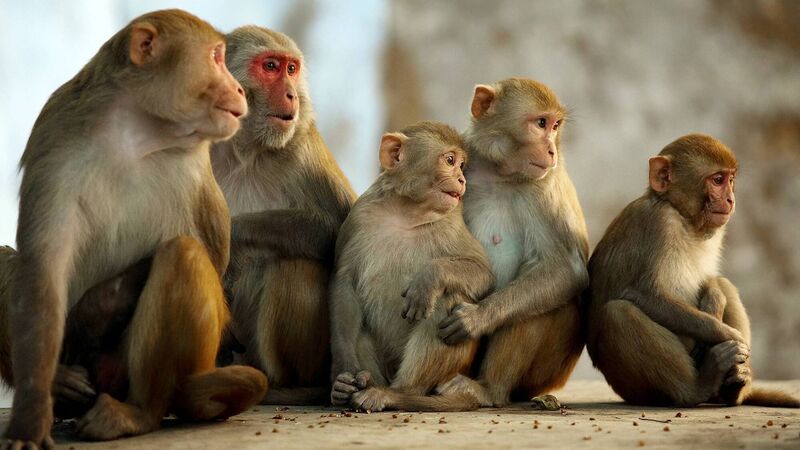

A 12-point stag, commanding his harem, would be Turlough’s equivalent among red deer. Likewise, the largest elephant seal bull rules the roost in a ‘rookery’. However, does being an alpha male, with virtually unimpeded access to compliant females, necessarily guarantee increased paternity? It has always been thought that it does, but a research paper, just published, challenges that assumption.