New book takes a look at the life and times of the aristocracy in the Georgian houses of Ireland

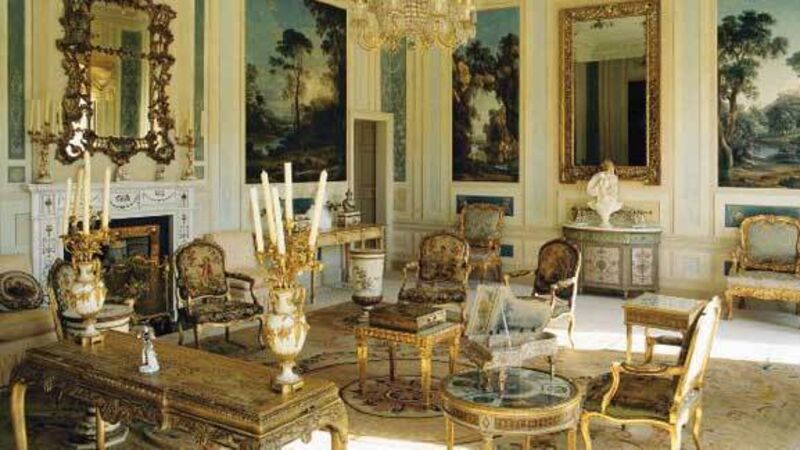

In Life in the Country House in Georgian Ireland, soon to be published by Yale University Press, architectural historian Patricia McCarthy takes readers into their world, explaining how and why they designed their homes the way they did, how they adorned them with the accoutrements of the rococco era, and what it was that made these houses, despite foreign influences, typically Irish.

And Irish they definitely were.