Feeder school data is misleading and old-fashioned

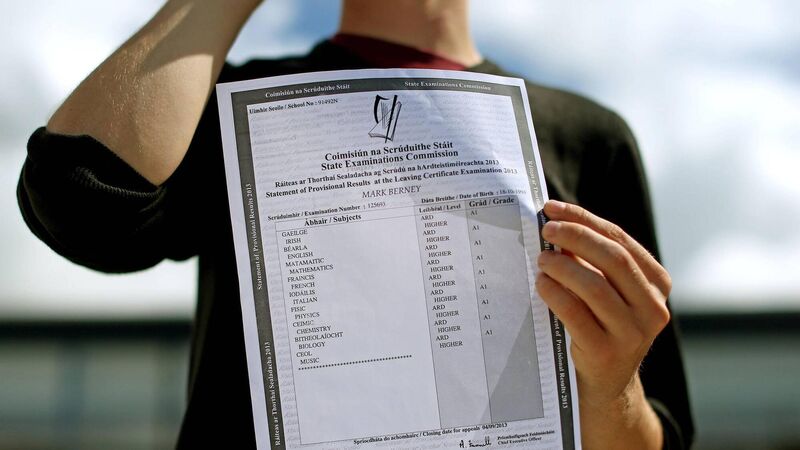

The continued prominence of feeder school rankings rests on an assumption that the primary purpose of second-level education is facilitating CAO entry to higher education, something seen as likely to improve future financial and social prospects. File photo

Each year, feeder school data ranks Irish second-level schools according to the proportion of students who progress to higher education via the Central Applications Office (CAO) system.

These tables appear to offer parents an objective basis for comparing schools. In practice, however, they provide a misleading account of what modern schools do and how young people now build successful futures.

Irish schools today educate unprecedented numbers of students with special educational needs, neurodivergent learners, and young people who use English as an additional language. Yet feeder school tables continue to define success through a single outcome: CAO entry to university.

This narrow framing obscures the complexity of schooling and privileges linear educational pathways that do not reflect many learners’ experiences.

Read More

The continued prominence of these rankings rests on an assumption that the primary purpose of second-level education is facilitating CAO entry to higher education, something seen as likely to improve future financial and social prospects. However, in a world marked by economic precarity, increased pluralism, and rapid technological change, this assumption is becoming less secure.

Traditional pathways are fragmenting and a university degree no longer guarantees stable employment or long-term security. This raises a pressing question for parents and policymakers alike: do feeder school tables offer an overly simplified account of school quality, one that reflects neither the diversity of students’ needs nor the changing economic and social futures they now face?

Feeder school tables do not measure the quality of schools; they tend to reflect the social and academic advantages of their students. Schools serving more affluent, academically prepared cohorts are rewarded, while those educating more diverse populations are systematically ranked lower, often regardless of the quality of teaching or support provided.

For many parents, feeder school data carries considerable weight in decisions about school choice. Progression rates are widely interpreted as indicators of effectiveness and future opportunity. Given the long association between higher education and social mobility, this response is understandable.

What the tables obscure is the range of factors shaping progression to higher education beyond schools. Socio-economic background, prior attainment, family expectations, language proficiency and disability status all exert a powerful influence on progression patterns.

When these factors are ignored, schools with inclusive intakes appear less “successful”, even when they are undertaking highly demanding educational work.

Some of the most effective inclusive work taking place in Irish schools is rendered invisible by feeder school tables. When success is defined solely as CAO progression, schools that support complex or non-linear educational pathways risk being systematically misrepresented as underperforming.

Around one in five pupils has an identified special educational need or learning difference, with many others requiring additional supports beyond formal diagnosis. For many, educational progress does not follow a linear trajectory. Reduced timetables, subject exemptions and supported examinations are often necessary and appropriate accommodations.

In a country that continues to record one of the highest disability employment gaps in Europe and the OECD, planned progression to further education, apprenticeships or supported employment may represent the most responsible outcome. These pathways represent effective and supportive educational practice rather than lower expectations.

Feeder school tables also routinely misinterpret delayed or non-CAO progression among students who use English as an additional language as educational failure. Academic English proficiency develops over time and often beyond the Leaving Certificate years.

For many students, progression to higher education is indirect, a predictable feature of language acquisition rather than a failure of schooling.

These students are disproportionately concentrated in ETB and DEIS schools, where staff invest heavily in language development, social inclusion, and pastoral support. When success is measured only through CAO entry, this work is discounted and responsible educational practice is mistaken for underperformance.

Feeder school tables are built around an increasingly outdated idea of post-school success. In an economy reshaped by automation and artificial intelligence, university is no longer the sole route to financial security or social stability.

Many vocational and technical roles are highly specialised, in demand and more resistant to automation. Meanwhile, returns on some graduate pathways have become less predictable, with professional and consultancy firms, formerly lucrative employers for graduates, dramatically reducing hiring as they rely on AI.

Education policy now places greater emphasis on lifelong participation, meaningful employment and community engagement, particularly for neurodivergent adults and people with disabilities. When feeder school tables continue to present immediate CAO progression as the gold standard, they misrepresent both the futures available to young people and the work schools are increasingly expected to do.

The purpose of education is to prepare young people to succeed in contemporary Ireland. Measures of school effectiveness must reflect current realities, rather than reinforcing a hierarchy that no longer serves many students or their communities.

- Dr Neil Kenny, School of Inclusive Education, Dublin City University