Grok's explicit image scandal highlights international legal flaws

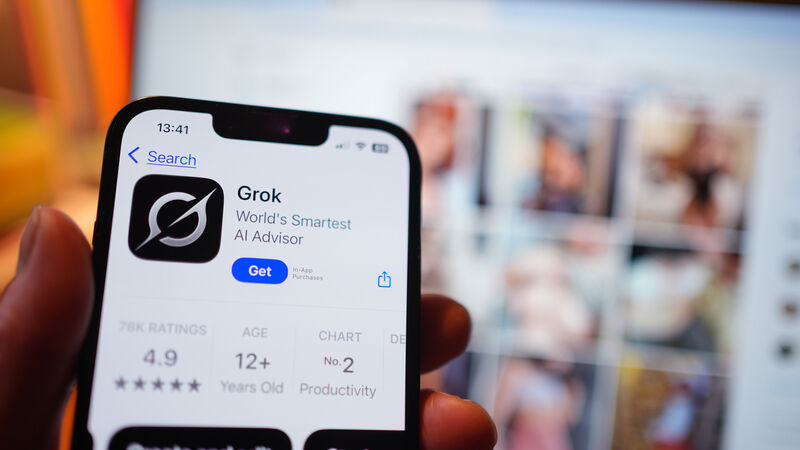

'An especially concerning aspect of the Grok story is that the AI system has been producing images in response to public messages on X, posting those images publicly on the platform.' File picture: Yui Mok/PA

Over the past number of weeks there has been a lot of debate about how Grok, Elon Musk’s generative AI system, has been used to produce sexualised images of women and children. This has been a truly shocking development.

An especially concerning aspect of the Grok story is that the AI system has been producing images in response to public messages on X, and posting those images publicly on the platform, without the consent of the person that is being depicted, and anyone can read the interaction with Grok which, in itself, is shocking.