Reforms must tackle judicial and public procurement processes to deliver infrastructure

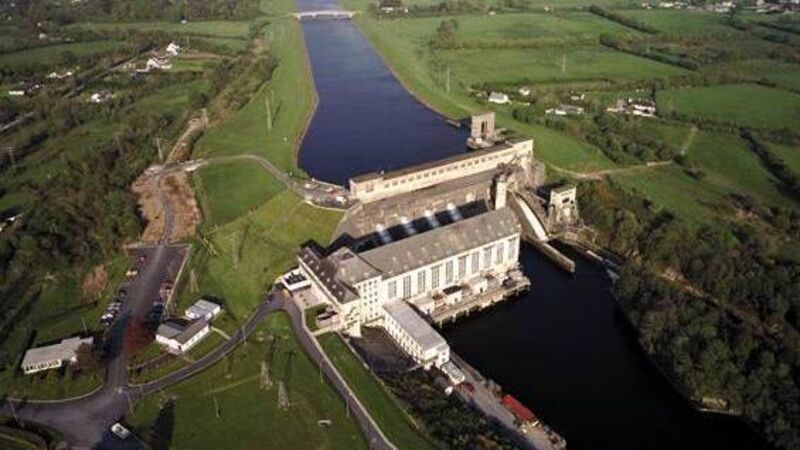

Ardnacrusha remains the most ambitious project the Irish State has ever achieved. File photo

Ireland was in a truly dire state in 1924 when Cumann na nGaedheal and Derry TD, Patrick McGilligan, observed: "There are certain limited funds at our disposal. People may have to die in this country and may have to die through starvation."

McGilligan was speaking in his role as the State's minister for industry and commerce and his quote highlights the grim reality facing the broken Irish Free State following years of state and intra-state warfare leading to the call to dump arms in 1923.