Gambling, obesity, alcohol: Is it time for industries to pay for impact of their goods on health?

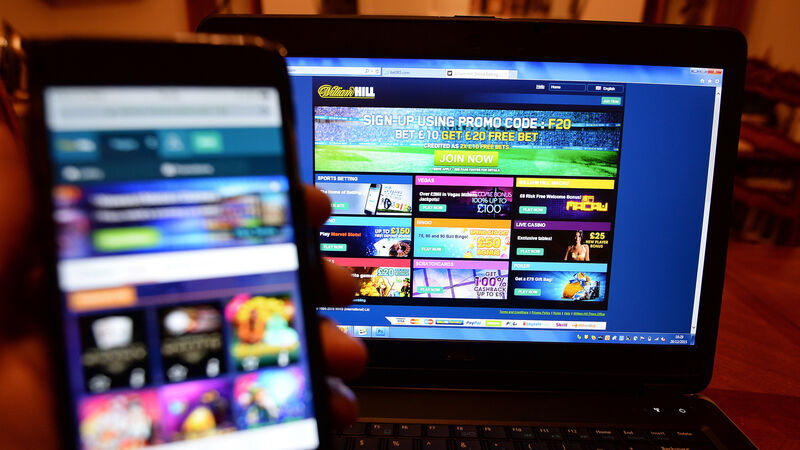

People with problem gambling spend on average more than €1,000 per month on gambling. Online gambling accounts for three-fifths of the total gambling spend of people with problem gambling, with in-person gambling accounting for the rest. File picture

Ahead of Budget 2024, is it time to consider how vastly profitable global corporations can be obliged to adopt a ‘polluter pays’ model that addresses the impact of their industry on health?