Power to the profit-makers: Letting big tech source energy directly raises questions of climate justice and democracy

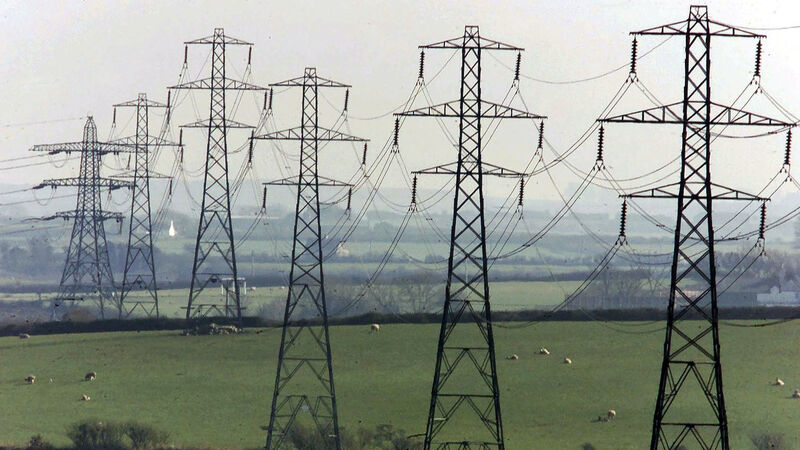

Private Wires is presented as facilitating the private sector to build grid infrastructure the State cannot provide. Picture: PA

In August, the Government published a consultation document on ‘Private Wires’.

Given the time of year and the boring title, it is no surprise that it received little attention beyond a few interested groups.