Paul Hosford: Ignorance of the Troubles a privilege afforded to me, but not to my grandfather

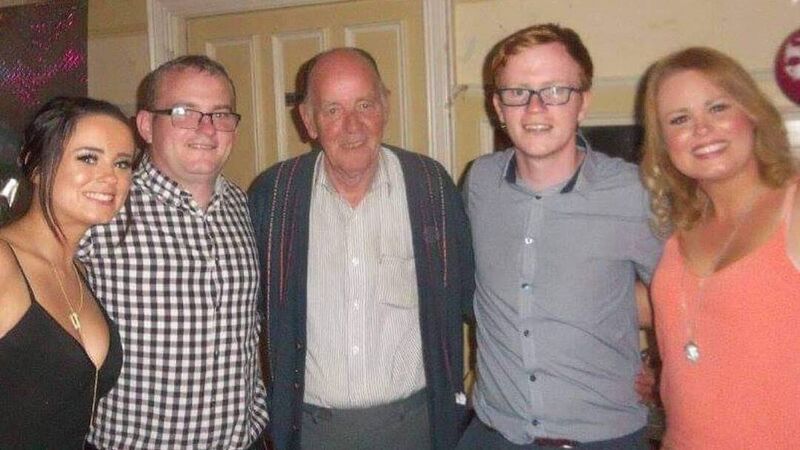

Paul Hosford with his grandfather Jim Stafford and his siblings Sinead, David, and Michelle.

I was around eight years of age when I first realised that my grandfather wasn't from Cork.

At that age, as a contrarian child who had taken the city of his birth to heart over the city his parents had moved to — Dublin — I couldn't conceive how someone who lived in Cork wouldn't be from there.