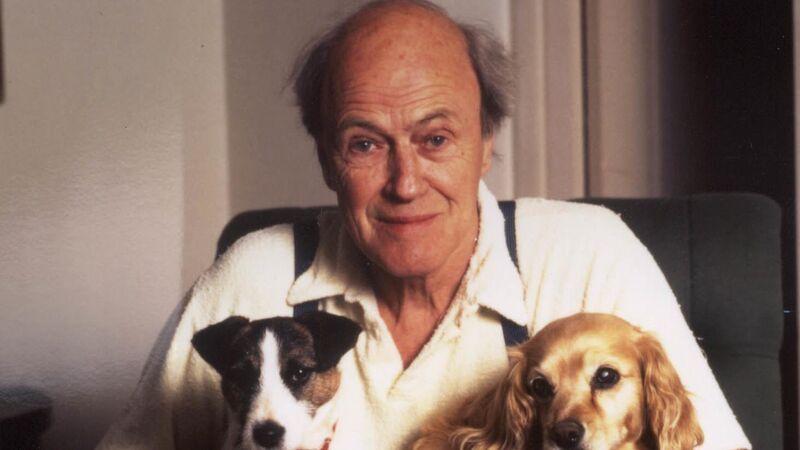

Roald Dahl rewrites: Instead of 'bowdlerising' his books, help children navigate history

The latest editions of Roald Dahl's children's books have been edited to remove language which could be deemed offensive.

Although several of his best-known children’s books were first published in the 1960s, Roald Dahl is among the most popular authors for young people today. The recent decision by publisher Puffin, in conjunction with The Roald Dahl Story Company, to make several hundred revisions to new editions of his novels has been described as censorship by Salman Rushdie and attracted widespread criticism.

The changes, recommended by sensitivity readers, include removing or replacing words describing the appearance of characters, and adding gender-neutral language in places.