Fusion energy: What does the recent breakthrough by scientists in California mean?

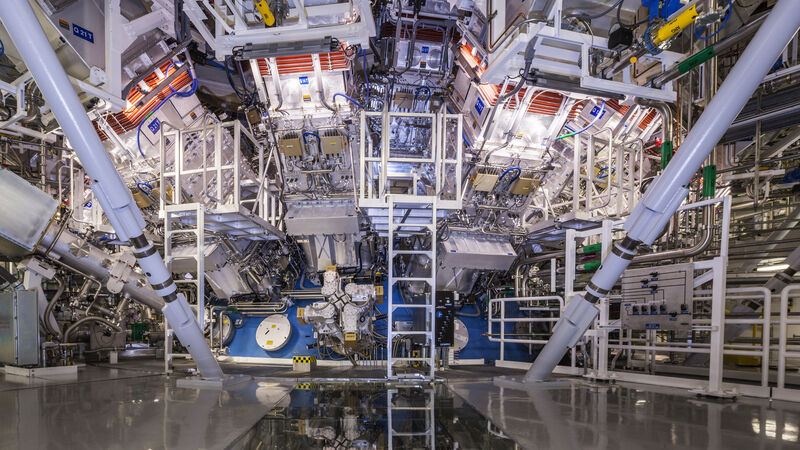

The ultimate goal of the research at the National Ignition Facility at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory is to construct fusion reactors that would provide electric generation capacity to ensure a stable supply in a post-fossil fuel world where most power will be generated by inherently volatile renewable energy sources. File picture: Damien Jemison/Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory via AP

Nuclear fusion is the process by which hydrogen and other light nuclei fuse together to form a larger daughter nucleus whose mass is slightly less than the sum of the parent nuclei masses. This “missing mass”, M, appears in the form of a large release of kinetic energy, ie energy of motion, via Einstein’s equation E = Mc where c is the speed of light.

Fusion is the energy source that powers all stars, including our Sun, and hence is essential for sustaining life on Earth.

CLIMATE & SUSTAINABILITY HUB