Ryan O'Rourke: Prison visiting is an experience of shame and powerlessness

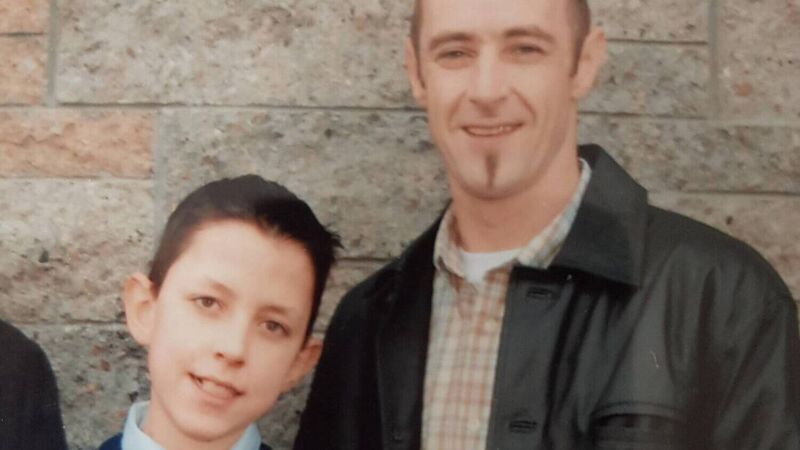

A 12-year-old Ryan O'Rourke and his father Brian, who was imprisoned for smuggling cannabis just three years later.

A heavy metal gate slides closed behind me, cutting off the only access to the outside world.

At the other side of the small, claustrophobic hallway in which I stand is another gate, which begins to open just as the first seals closed.