Ronaldo Munck: Irish universities need to set new priorities after Covid pandemic

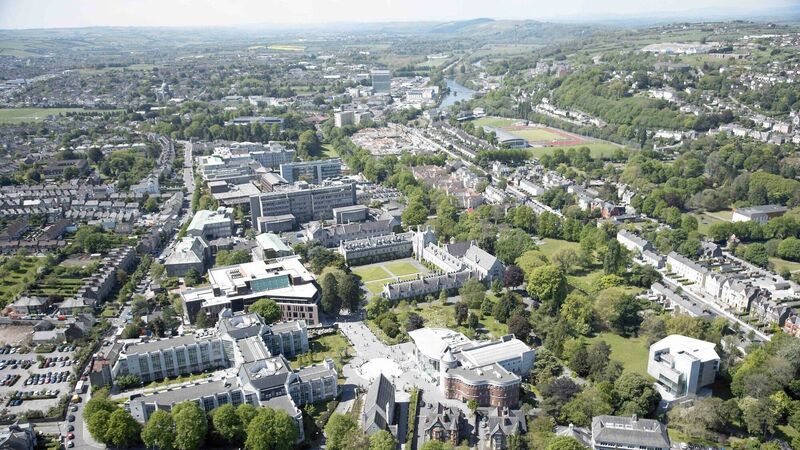

An aerial view of the UCC campus. File picture: UCC

There is a strong tendency after any crisis to want to ‘get back to normal’. A new book, with a strong Irish input, , argues, however, that this is neither possible nor desirable.

A crisis — as we have all learnt through living with Covid for a year now — is in fact a turning point in a disease. There is either recovery and renewal or a deepening of the illness and possibly death. There can be no return to the status quo and ‘business as usual’ is simply not an option for higher education, any more than for society as a whole.