Biden's battle over Rescue Plan Act only just beginning

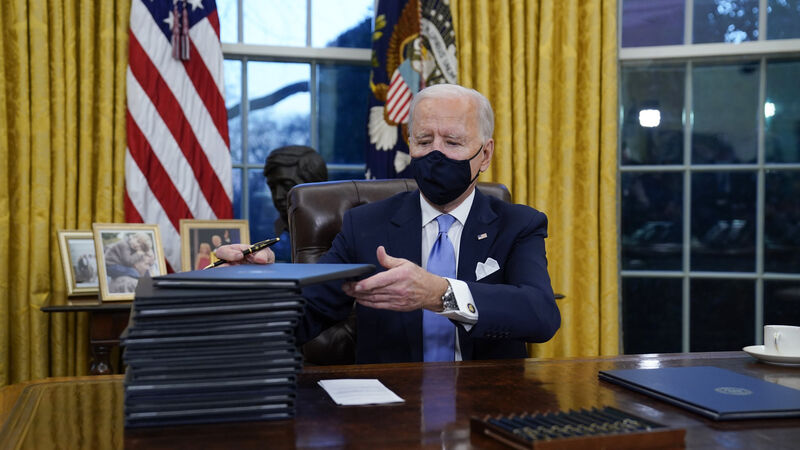

President Joe Biden last week signed into law the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, one of the most ambitious domestic-policy legislation ever passed. Picture: Evan Vucci/AP

The most significant thing that US president Joe Biden said in his first prime-time address last week was that, in recent years, “we lost faith in whether our government and our democracy can deliver on really hard things for the American people”.

It was now up to the slim, seemingly unassuming Mr Biden, after decades of seeking the Oval Office, to show that America is governable.