Analysis: Leaving Cert results raise important gender bias issues

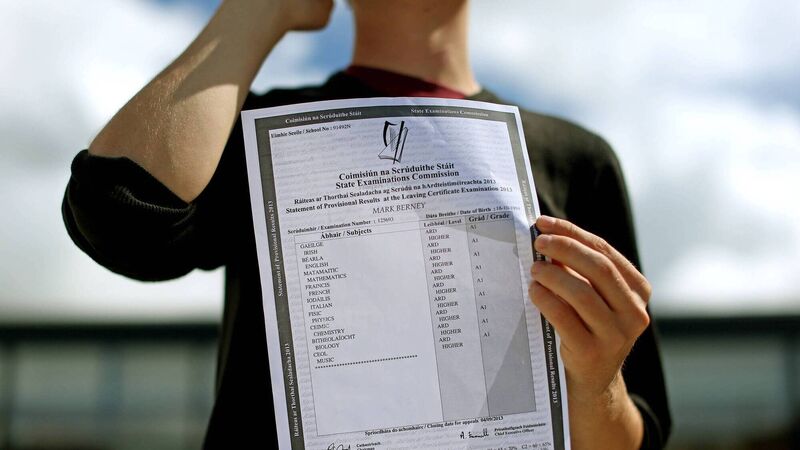

The final Leaving Cert grades are 4.4% on average higher this year than in previous years. File image

The Leaving Certificate was cancelled on May 8 to be replaced by the teachers’ subjective judgments on what percentage mark they thought each of their students might have received in the Leaving Certificate.

They also gave their ranking of each student relative to their peers, with oversight by their school principal.