In God’s name? The politicisation of religion and potentially deadly consequences

charts the politicisation of religion and the potentially deadly consequences.

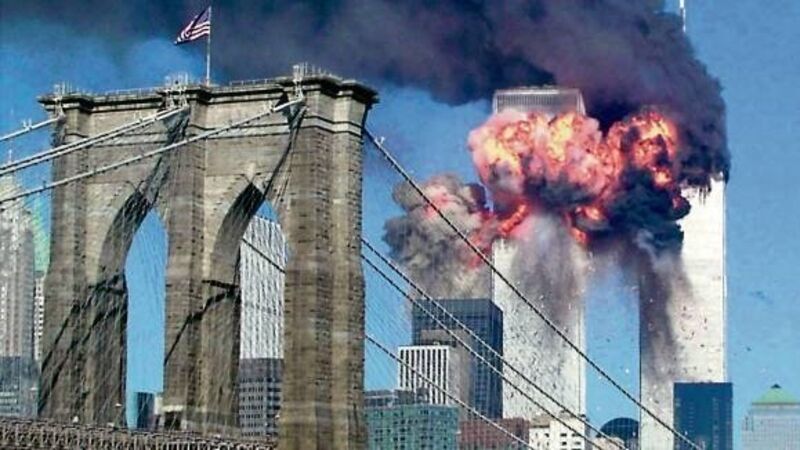

The bitter divisions, the bloody conflict, the sectarianism, bigotry, and pervasive mistrust that have been so much a part of the fabric of the North since partition were fuelled in large measure by a phenomenon we have come to a new appreciation of in the post-9/11 age — political religion.