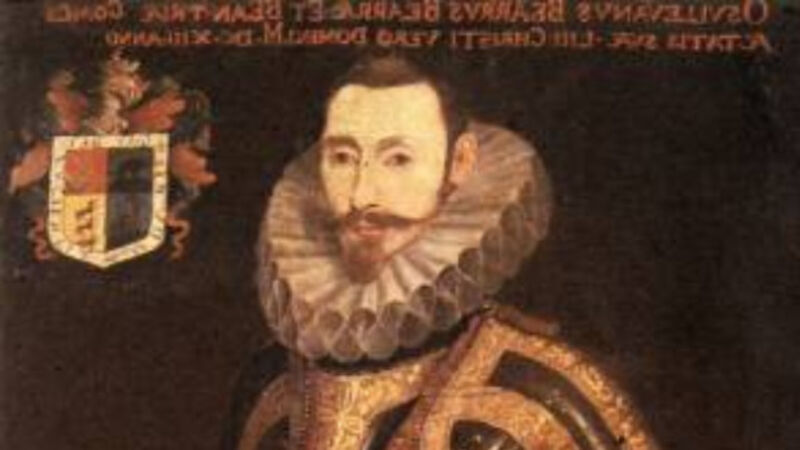

400 years ago this summer, the great leader O’Sullivan Beare had his throat cut in Spain

DONAL Cam O’Sullivan, chief of Beara, had his throat cut in Madrid 400 years ago this summer. It happened in Plaza de Santo Domingo, near the royal palace, on July 16, 1618.