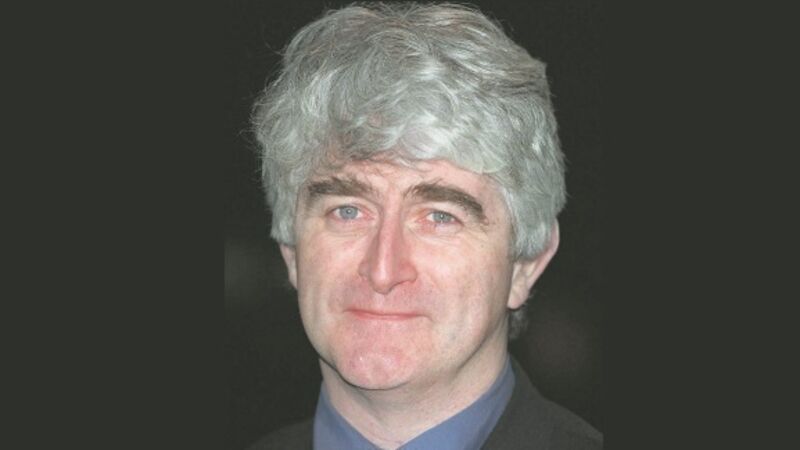

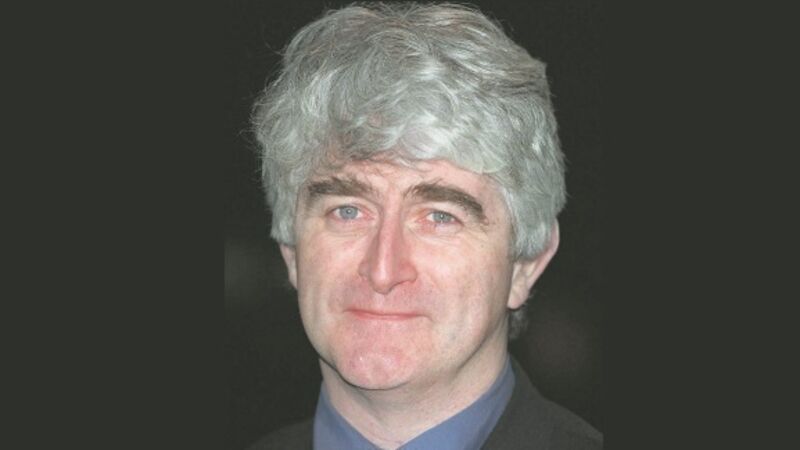

Dermot Morgan's son says he knew how to be one hell of a Father, Ted

Since my first son was born in 2015, I have been trying to understand my new role in the absence of my own father, Dermot Morgan, who today will be dead 20 years.

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBE

Dermot Morgan died 20 years ago today. His son, Don Morgan, says that his father greatly influenced how he raises his own sons, and why he hopes they will grow up to be feminists

Since my first son was born in 2015, I have been trying to understand my new role in the absence of my own father, Dermot Morgan, who today will be dead 20 years.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.

Newsletter

Keep up with stories of the day with our lunchtime news wrap and important breaking news alerts.

Newsletter

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.

Saturday, February 7, 2026 - 7:00 PM

Saturday, February 7, 2026 - 5:00 PM

Saturday, February 7, 2026 - 5:00 PM

© Examiner Echo Group Limited