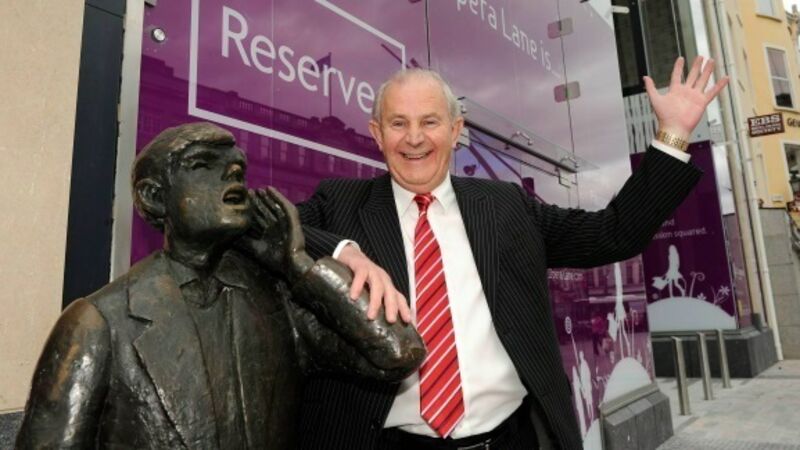

Developer Owen O'Callaghan has left a legacy across the Irish skyline

Tue, 24 Jan, 2017 - 00:00

Tommy Barker, Eoin English & Sean O'Riordan

‘City has lost one of its champions’

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Subscribe to access all of the Irish Examiner.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

CourtsAnalysisowen ocallaghanDevelopmentMahon Pointopera lanearthurs quayMerchants QuayPlace: CorkPlace: MahonPlace: Mahon PointPlace: Temple Hill Funeral HomePlace: Boreenmanna RdPlace: St Patrick’s ChurchPlace: RochestownPlace: St MaryPlace: St John Churchyard Cemetery, BallincolligPlace: UKPlace: IrelandPlace: Mahon Point Shopping Centre and Retail ParkPlace: Opera LanePlace: Half Moon StPlace: Anderson’s QuayPlace: Emmet PlacePlace: Johnson andPlace: Academy StPlace: Lee tunnelPlace: St Patrick’s StreetPlace: Paul Street Shopping CentrePlace: North Main Street SPerson: Owen O'CallaghanPerson: Owen OPerson: CallaghanPerson: Owen O’CallaghanPerson: O’CallaghanPerson: Lord Mayor Des CahillPerson: IndependentPerson: Kieran McCarthyPerson: Terry ShannonPerson: Lawrence OwensPerson: CEOPerson: Barry O’ConnellPerson: ShelaghPerson: BrianPerson: ZeldaPerson: HazelPerson: Tommy BarkerPerson: Opera LaneEvent: ChristmasOrganisation: Fianna FáilOrganisation: Cork Business AssociationOrganisation: Cork ChamberOrganisation: AppleOrganisation: CSPCAOrganisation: Dunnes StoresOrganisation: Roches StoresOrganisation: Merchants QuayOrganisation: Marks and