The compelling story of how Irish diplomacy saved the life of a man of courage

ON MARCH 24, 1976, the Argentine military staged a coup d’etat, overthrowing a civilian government, and setting in train an internal war which determined to eliminate all opposition — including opposition from sections of the Catholic Church identified with progressive thinking.

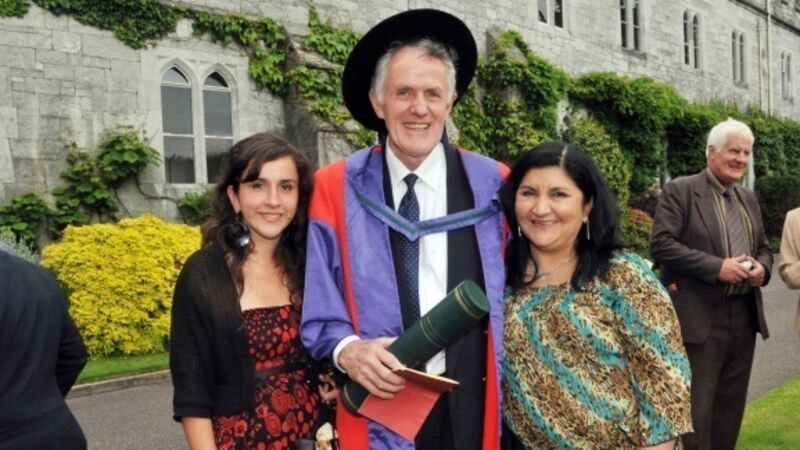

Patrick Rice was one such target. After coming to the country in 1970 as a Divine Word Missionary, he joined the Little Brothers of Charles de Foucauld and made his living as a carpenter on a building site while working and living as a priest in a shanty town, Villa Soldati, in Buenos Aires. He was also the leader of his congregation in the country.