Special Report (Rural Ireland): Ballydehob punching above its weight yet again

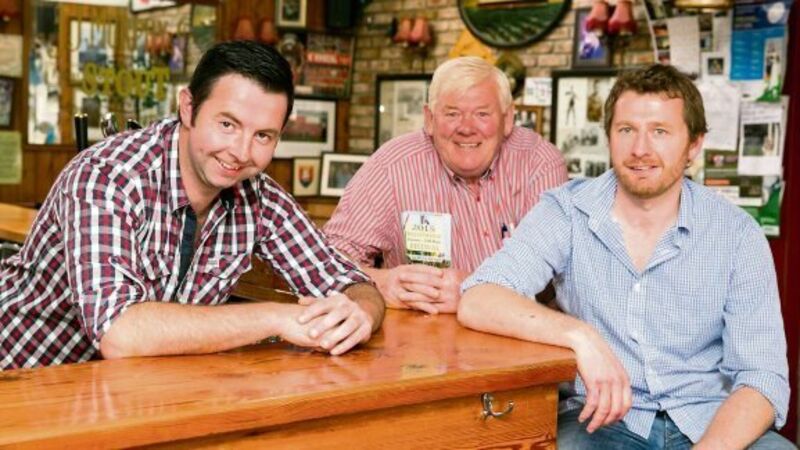

When Barry O’Brien landed in Ballydehob, there were 11 shops in which you could buy groceries. That was back in 1990. O’Brien was looking for a business that could support his young family, and found it in a pub in the small West Cork village.

There were ten pubs in the hamlet at that time. “There would be somebody in from opening time at 10.30am,” O’Brien says. “Farmers on their way to or from mart day in Skibbereen, a lot of them sheep farmers. And men would drop in for a few pints here and there. There was always some bit of trade.”