Words that came back to haunt nation

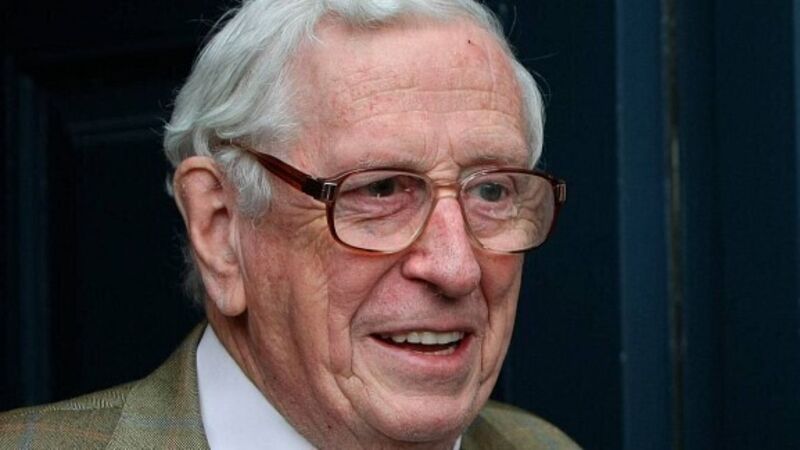

GARRET FITZGERALD agreed with the Pro-Life Amendment Committee in 1981 that a constitutional amendment was necessary to ensure that abortion could not effectively be legalised by a court ruling as had happened in the United States.

The Fianna Fáil government released the wording for this referendum on Nov 2, 1982: “The State acknowledges the right to life of the unborn and, with due regard to the equal right to life of the mother, guarantees in its law to respect, and as far as practicable, by its laws, to defend and vindicate that right.”