Colin Sheridan: How strange that courage is celebrated in death and reviled in life

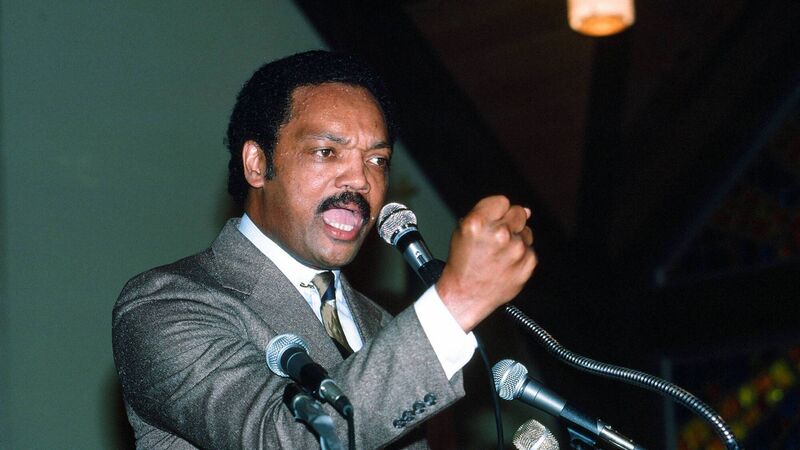

Jesse Jackson stood on the front lines of America’s most combustible moral battles. He took the blows — literal and figurative — and watched his comrades fall. Picture: Robert R McElroy/Getty

Oh, obituary! Like your bedfellow the eulogy, you serve that magical purpose of allowing people to say things about you in passing they would never in life.

You permit the living to write the history of the dead — not as factum, but as a projection of what they want to believe.

A hallelujah for those they can now praise without consequence; a pious nod to those whose fiercest adversaries are gone.

This week, the death of the Reverend Jesse Jackson touched off precisely this spectacle: A cascade of encomia from corners of the polite establishment that once did everything in their power to dismiss, demean, and, at times, criminalise him.

Jackson stood on the front lines of America’s most combustible moral battles. He took the blows — literal and figurative — and watched his comrades fall.

And yet, now that the fire has gone out, the same forces that scarred him with sneers and subpoenas clasp hands in solemn remembrance.

How strange that courage is celebrated in death and reviled in life.

Tributes to Jackson are easy now because he is no longer a threat.

Safe in the archives of civil-rights lore, he has been scrubbed of what made him dangerous — the militancy, the impatience with polite consensus, the critique of power that made him a foil to both parties in Washington and beyond.

In the 1960s and 1970s, cheering Jackson was to court invective and invite suspicion; in 2026, it is to display virtue without risk.

There is a grotesque inversion here: The man once tarred as an agitator is now folded into the moral memory of a society still wrestling with the contradictions he exposed.

If Jackson’s retrospective praise reveals the dissonance of establishment respect, consider the contempt directed at Francesca Albanese — the UN special rapporteur on the occupied Palestinian territories.

Albanese does today what Jackson did then: She speaks truth to power. She names injustice plainly. She refuses the comfort of diplomatic euphemism in the face of oppression. She does it pro-bono, evidence she can’t be bought.

And for that, she is vilified by establishment figures, government politicians, men generally.

This week, renewed calls for her dismissal erupted — not over evidence of wrongdoing, but over fabricated comments and mischaracterisations of her work.

“The fact that there’s more scrutiny over something I didn’t say than over the practices of a state accused of crimes against humanity and genocide is telling,” the rapporteur told Euronews after several European foreign ministers — including those of France, Germany, Austria, Italy, and the Czech Republic — publicly called for her resignation after a doctored clip circulated on social media claiming that she had described Israel as the “common enemy of humanity”.

In fact, the full, unedited recording shows she never made that statement and was referring broadly to the system that enables mass violence, and numerous rights experts and UN bodies have since condemned the accusations as manufactured and misleading.

It is, plainly, a smear. And it is a smear that has followed her for as long as she has spoken for Palestinian rights — a cause as divisive today as civil rights were in Jackson’s America.

To many in the establishment, speaking unequivocally about occupation and dispossession is not human-rights advocacy but a provocation to be quelled.

Here lies the shared pattern: When truth threatens power, the first response is to discredit the truth-teller.

The comparison is not to collapse context. Their histories and struggles are distinct. But the dynamic — how institutions respond to sustained critique — reveals an eerie symmetry.

Jackson was branded unpatriotic and dangerous for insisting America confront its racial sin. His life was routinely targeted. He was surveilled by the FBI, mocked in Congress, portrayed as a demagogue whose moral urgency unsettled the comfortable.

Albanese today faces a campaign to delegitimise her work, to depict her not as a human-rights expert raising recognised principles but as a provocateur unworthy of her post.

The same sophistry — innuendo dressed as critique —mirrors the tactics that once greeted Jackson’s agitation.

Yet observe how differently they are treated once the stakes shift. Jackson’s critics now speak of him in golden tones because it is safe.

The forces that once tried to clip his wings have, with distance and diminished threat, wrapped him in commemorative fleece.

Albanese, however, remains in the white-hot glare of controversy. Her detractors wish she would vanish — not because of verifiable misconduct, but because her moral insistence unsettles them.

That is not coincidence. It is the reflex of power when confronted with unbending clarity. What does it say about us that we celebrate a fiery insurgent in death but vilify one in life? That we frame an outspoken Black civil-rights leader as a triumph in hindsight, while casting a woman advocating human rights as an embarrassment today?

The answer begins with fear.

Institutions, like individuals, fear sustained moral challenge. They whisper and deflect because they cannot answer the central question: Is this just? Or are we defending the indefensible?

In Jackson’s time, the question was whether Black Americans were entitled to equal dignity. The answer came slowly, and not without backlash.

In Albanese’s time, the question is whether Palestinians are entitled to the same protection of basic international law afforded to others.

The ferocity of the response tells us how power manages dissent.

We must also be honest about something else: Neither Jackson nor Albanese is perfect. Saints they were not, nor should they be.

Human beings of conscience are messy and complicated because conscience itself is not a tidy thing.

I wrote recently in these pages about how the veneration of Noam Chomsky — rightly admired for his critique of power — nonetheless obscured his astonishing misstep in aligning himself with Jeffrey Epstein, a monied predator that Chomsky’s own politics should have condemned without hesitation.

Leaders are flawed. Moral clarity does not confer moral infallibility.

But imperfection does not justify smear after smear. It does not excuse the refusal to engage with substance rather than personality.

Jackson’s critics reduced him to caricature because they could not counter his moral force. Albanese’s critics do the same, attacking the messenger because the message — that human rights are universal and violated with impunity — cannot be answered without the sting of complicit discomfort.

So let us be clear: The establishment’s late affection for Jackson testifies to how threatening his truth once was.

And the hostility toward Albanese testifies to how threatening hers remains.

If Jackson were at the height of his power today, he would be shouting just as loud as Albanese — and just as hated for it.

Instead, he is dead, and because it is convenient, he is lauded.

Power embraces insurgents only once they are safely interred. The truest tribute to Jackson is not obituary praise, but recognition of the pattern: Moral courage threatens power; advocates of justice are discredited before they are celebrated; and history is written first by those with weapons, and only later — if at all — by those with conscience.