Paul Hosford: Best for John Moran and Limerick councillors to refocus and just get on with it

Limerick mayor John Moran described how a minority of councillors from Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael have ‘consistently opposed almost every significant initiative’ he has brought forward.

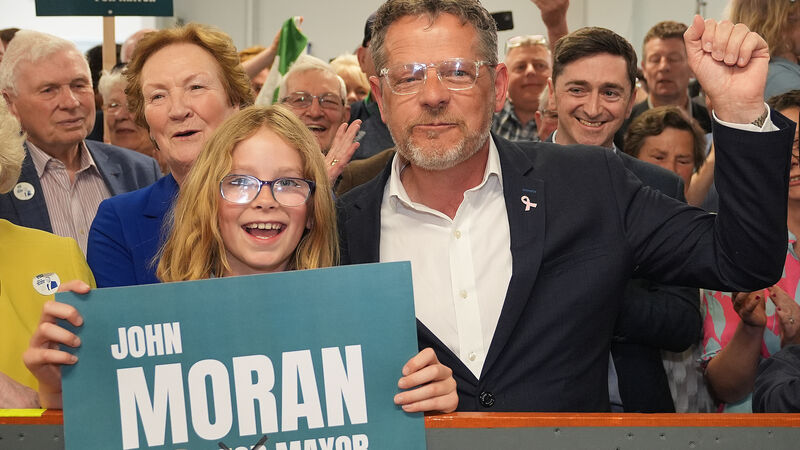

Just over a year and a half ago, as John Moran was inaugurated as the first-ever directly elected mayor of Limerick, the future of local democracy in Ireland seemed very different.

The Limerick experiment, five years in the making and much-hyped, had the opportunity to be transformative not just for the Treaty City but for country’s other cities — Dublin aside.

While the notion of handing over the reins of the capital to any one person is something that very few in Government will ever countenance, five years of the Limerick version working would surely have opened the door (and some minds) about how it could work in Cork, Galway, and Waterford.

However, that optimistic outlook for those who advocated executive functions at local level looks to have been shattered after a week of recriminations in Limerick.

On Monday, sharing details of what happened at a seven-hour-long meeting last week during which he took ill, Mr Moran released a blog post in which he accused councillors of blocking his work.

In the statement, Mr Moran described how a minority of councillors from two “ruling” parties — Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael — have “consistently opposed almost every significant initiative” he has brought forward.

He also told readers how a “strategy” was openly discussed on how to make his role “unbearable”.

He referred to claims of a “culture of fear” inside the council, pointing out the “difference between robust debate and personal hostility”.

“When disagreement becomes dismissive or mocking — when serious health concerns are reduced to trivial language and not accommodated — it diminishes the very institution itself,” he wrote.

Last resort

It was an extraordinary missive, one which bore the hallmarks of a last resort. However, it also bore the hallmarks of one which didn’t seem to have a next step in mind.

On Wednesday, Mr Moran said he was “advised to walk away” from his mayoral role.

Limerick Labour TD Conor Sheehan said that a mediator must be appointed to resolve the “mayoral stasis” in the county.

Mr Sheehan, who was Labour’s candidate in the 2024 election, called on the Government to urgently bring forward a legislative review of the directly elected mayor of Limerick, and he urged the Government to appoint an independent mediator to resolve the ongoing standoff at Limerick’s City Hall.

Just over 20 months in, the fact that anyone is calling for a mediator is not a great sign of success.

Mr Sheehan’s intervention also hit at one major part of the problem, railing against the “clear weaknesses and ambiguities in the legislation governing the directly elected mayor” that, he claimed, were “at the heart of this dysfunction”.

These flaws were repeatedly flagged by opposition TDs, but the final legislation was watered down, leaving uncertainty over where executive authority lies and who is ultimately responsible for key governance decisions within the council

The Labour TD is not alone in his assessment. MEP Michael McNamara said that the mayor “has less power than the CEO of Cork [City Council], where the people rejected a directly elected mayor in a plebiscite”.

“It was clear from the outset that the role envisaged for the mayor of Limerick under the law passed in 2023 could not succeed and now needs to be reviewed. Those in the Custom [House] who created this mess because of their fear of decentralising power should hang their heads, even though they’ve won,” he posted on X.

Many in opposition made these points when the legislation was published in 2023, and a report by two senior parliamentary researchers in the same year now looks prescient.

The report pointed to previous research which suggested that the position was being created “within the context of a highly-centralised State”, where the scope for policymaking at local level is somewhat limited.

“Comparative research highlights problems when a mayor has a popular mandate, but little power can be frustrating and confusing for people,” it said.

“There is some concern that the envisaged strategic policy role for the mayor will be difficult to realise without greater access to finance and devolved powers.”

Dodged a bullet

Those public representatives who missed out as Mr Moran swept to power in 2024 may now feel that they have dodged a bullet of sorts, with one Limerick politician saying this week that “Jesus himself” would have struggled to work within the confines of the role.

Mr Moran’s issues with the council have been obvious for some time, and there are a number of reasons why: Weak legislation, funding, people fighting for their own patch of land, and personalities.

Asked about the row on Wednesday, junior finance minister Robert Troy said it came down to “people that don’t get on”.

“Sometimes it’s just down to basic personalities and people that don’t maybe get on very well with other people,” he said.

What I would say is it’s [up to] both the directly elected mayor and individually elected councillors to work together for the betterment of Limerick

Mr Troy is correct, according to multiple sources, in that there is an element of the row that comes down to people not liking each other enough to put political differences to one side.

But that idea will seem strange to the public, when the average person has to go to work with people they might not like and just, quite simply, get on with it.

For Limerick, the chance at a transformative office spearheaded by one accountable person seemed too good to miss. It is certainly too good to be derailed because of personality clashes, especially when you consider the knock-on effects.

Clear democratic mandate

Directly elected mayors could play a transformative role in strengthening governance and accountability in Irish cities, providing a clear democratic mandate, and offering a visible figurehead responsible for delivering on transformation of urban areas.

Every city faces complex challenges from housing shortages, transport congestion, climate adaptation, and economic competitiveness. A directly elected mayor with executive powers could co-ordinate long-term planning behind a coherent vision. For the denizens of cities who feel that the growth of Ireland is the growth of Dublin, what better chance than having one person driving and advocating on your behalf?

In Limerick, it is essential that all sides allow calmer heads to prevail — including allowing mediation.

Local government, any level of government really, functions best when disagreements are handled with restraint, mutual respect, and a shared focus on the public good.

By stepping back from personalisation and refocusing on Limerick’s long-term interests, those involved can demonstrate the maturity and leadership that people expect from their elected representatives.

There are three and a half years left in the term of Mr Moran, and there is too much work to be done for a clash of personalities to be the reason the office fails.

Subscribe to access all of the Irish Examiner.

Try unlimited access from only €1.50 a week

Already a subscriber? Sign in

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates